This Research Paper has been co-authored by Ananya Atri and Falguni Mahajan. You’ll find a downloadable version of the paper at the end. We wish you an insightful read and hope to hear from you in the comment section.

Learning Outcomes:

- Understand the concept of feminist foreign policy (FFP) and its core values.

- Examine case studies of countries that have implemented feminist foreign policies.

- Discuss the obstacles and challenges in implementing a feminist foreign policy, including societal biases, resistance from male resentment, the need for nuanced approaches in various policy areas, and difficulties in monitoring progress

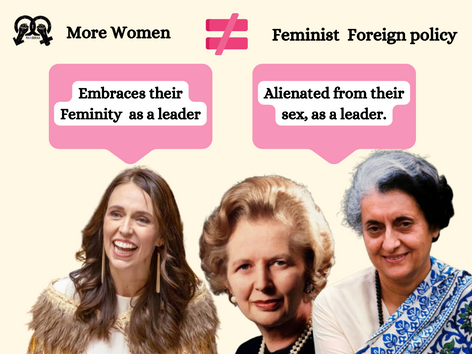

Theorising Feminist Foreign Policy

“Feminist Foreign Policy is the policy of a state that defines its interactions with other states and movements in a manner that prioritises gender equality and enshrines the human rights of women and other traditionally marginalised groups, allocates significant resources to achieve that vision, and seeks through its implementation to disrupt patriarchal and male-dominated power structures across all of its levers of influence (aid, trade, defence, and diplomacy), informed by the voices of feminist activists, groups, and movements.”

- (Leric & Clement, 2019, 7)

But before the authors chime in, they seek to theorise feminist foreign policy.

Ethics of care

Why does all of this concern the foreign policy of the state? Well, unsurprisingly, emotions do play a prominent role in International Relations because, ultimately, diplomacy is itself an art-play of Individuals. (Check out Should You Be Emotional?: A Look Into The Power of Emotional Diplomacy.)

Intersectionality (Find out: What’s Intersectionality?)

Gender Mainstreaming (Find Out: What’s Gender Mainstreaming?)

Core Feminist Foreign Policy Values

Inspiring Change: FFP’s Case Studies from Sweden to Mongolia and Beyond

Can India aspire for such a change?

“The idea of FFP needs to be tailored to each country’s specific political needs and backgrounds, making it all the more important for India to derive its own definition of the concept.”

- Magan (2022)

Feminist Foreign Policy's Obstacles

While there are many more issues, we can sum all of them under one banner: How can a Feminist Foreign Policy ensure that it is nuanced everywhere, all the time? (A claim made by the Swedish government)

Conclusion

Download the Paper here:

References

- Aggestam, Karin, Annika Bergman Rosamond, and Annica Kronsell. “Theorising feminist foreign policy.” International Relations 33, no. 1 (2019): 23-39. Retrieved July 13, 2023 from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0047117818811892.

- Atri, Ananya. “Blog Post | Tackling Gender Disparity at the Diplomatic Table”. Mandonna (2023). Retrieved on July 7, 2023 from https://www.mandonna.co.in/post/tackling-gender-disparity-at-the-diplomatic-table

- Brechenmacher, Saskia. “Germany Has a New Feminist Foreign Policy. What Does It Mean in Practice?”. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2023). Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/03/08/germany-has-new-feminist-foreign-policy.-what-does-it-mean-in-practice-pub-89224.

- Cheung, Jessica, D. Gursel, Marie Jelenka Kirchner, and Victoria Scheyer. “Practicing feminist foreign policy in the everyday: a toolkit”. Heinrich Böll Stiftung (2021).

- CRS India. “Gender Mainstreaming in the Foreign Policy of India.” (2023). Retrieved from https://www.csrindia.org/gender-mainstreaming-in-the-foreign-policy-of-india/#:~:text=Gender%20mainstreaming%20in%20the%20Foreign%20Policy%20or%20a%20Feminist%20Foreign,and%20a%20more%20peaceful%20world.

- Equality Fund. “Our Herstory”. (2021). Retrieved July 6, 2023 from https://equalityfund.ca/who-we- are/our-herstory/

- Government of Spain. “Spain’s Feminist Foreign Policy: Promoting Gender Equality in Spain’s External Action” . (2021). Retrieved July 6, 2023 from http://www.exteriores.gob.es/Portal/es/SalaDePrensa/Multimedia/Publicaciones/Documents /2021_02_POLITICA%20EXTERIOR%20FEMINISTA_ENG.pdf

- Government of The Netherlands. “News | Feminist foreign policy explained”.(2022). Retrieved July 9, 2023 from https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2022/11/18/feminist-foreign-policy-netherlands

- Julia, Ricci. “Toward the adoption of a feminist foreign policy in India?”. Gender Institute in Geopolitics (2023). Retrieved on July 12, 2023 from https://igg-geo.org/?p=11200&lang=en.

- Mahajan, Falguni. “Media Bias: Women in Politics Pay Price.” Mandonna (May 26, 2023). Retrieved July 13, 2023 from from https://www.mandonna.co.in/post/now-you-can-blog-from-everywhere.

- Mahajan, Falguni. “Should You Be Emotional?: A Look into the Power of Emotional Diplomacy.” LinkedIn (2023). Retrieved July 13, 2023 from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/should-you-emotional-look-power-diplomacy-falguni-mahajan/.

- Marie-Cécile Naves. “Feminist foreign policy explained”. Sustainable Development News (2020). Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://ideas4development.org/en/feminist-foreign-policy-explained/

- Robinson, Fiona. “Feminist foreign policy as ethical foreign policy? A care ethics perspective.” Journal of International Political Theory 17, no. 1 (2021): 20-37.

- Rosa Stienstra. “Blog Post | Feminist Foreign Policy: A new and necessary approach to foreign policy and diplomacy”. Universiteit Leiden (2022). Retrieved on July 10, 2023 from https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/hjd/news/2022/blog-post—feminist-foreign-policy-a-new-and-necessary-approach-to-foreign-policy-and-diplomacy

- Tapakshi, Magan. “A closer look into Feminist Foreign Policy in India”. Observer Research Foundation (2022). Retrieved on July 10, 2023 from https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/a-closer-look-into-feminist-foreign-policy-in-india/

- The Gender Security Project. “ Mongolia’s Feminist Foreign Policy.” (2023). Retrieved on July 13, 2023 from https://www.gendersecurityproject.com/post/mongolia-s-feminist-foreign-policy

- Thompson, Lyric, and Rachel Clement. “Defining feminist foreign policy.” International Centre for Research on Women 2 (2019). Retrieved July 10, 2023 from https://www.wo-men.nl/kb-bestanden/1625575142.pdf

- Thompson, Lyric, Spogmay Ahmed, and Tanya Khokhar. “Defining feminist foreign policy: A 2021 Update.” International Center for Research on Women (2021). Retrieved on July 11, 2023 from https://www.icrw.org/publications/defining-feminist-foreign-policy/

- Tishya, Khillare. “The Feminist Foreign Policy Agenda: What is It and Why Should India Engage with It?. Heinrich Böll Stiftung Regional office New Delhi (2023). Retrieved on July 4, 2023 from https://in.boell.org/en/feminist-foreign-policy01

- Walfridsson, Hanna. “Sweden’s new government abandons feminist foreign policy.” Human Rights Watch (2022). Retrieved on July 5, 2023 from https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/31/swedens-new-government-abandons-feminist-foreign-policy

Authorship Credits

Falguni Mahajan is a graduate of Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University. Her interests are multi-faceted and everything about Gender, International Relations & Social Entrepreneurship is what activates her mind and soul. She envisions a space of inclusivity and equity and Mandonna is her first attempt to do just that!

Ananya Atri is an International Relations student and currently interns at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research at her university. She has been part of Global Youth India and right now serves as the Director of Communications at NGO Cultural Diversity for Peaceful Future in Georgia. Her interest in writing for Mandonna stems from her belief in equality and inclusion.