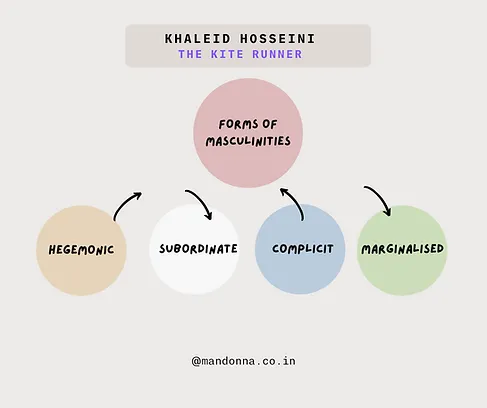

Amir, Hassan, Rahim Khan, Baba, Sohrab, Ali, and Assef are just a few of the many male characters present in the novel. The vast differences between all the male characters allow the readers an insight into the various forms of masculinities that exist around us.

“A look of disgust swept across his rain-soaked face. It was the same look he’d give me when, as a kid, I’d fall, scrape my knees, and cry. It was the crying that brought it on then, the crying that brought it on now.

“You’re twenty-two years old, Amir! A grown man! You . . .” he opened his mouth, closed it, opened it again, and reconsidered. Above us, rain drummed on the canvas awning. “What’s going to happen to you, you say? All those years, that’s what I was trying to teach you, how to never have to ask that question.” (Hosseini, 2003)

However, before we dive into Hosseini’s world and explore just how complex his characters are, it is necessary to familiarise ourselves with some key terms that this article uses. When the majority of studies, as well as fields, cater to men, resulting in the occasional focus on women, “What exactly does it mean to be a man?”— is not a question that one comes across frequently. Perhaps an even more difficult question to seek an answer to is “What is masculinity?”

Just as gender issues are not synonymous with ‘women’ problems, men cannot be equated with masculinity either. One’s location with respect to their caste, sexuality, queer, or patriarchal norms plays a role in defining the masculinity that one will inherit or exert. Masculinity is manifested in a myriad of ways, including but not limited to— social interactions, division of labour, manners of speech, gestures, behaviours, clothes, and even the way in which a person walks. While one community may approve of physically extensive labour as a masculine job, others may see “desk jobs” as more suitable and masculine for men; bulky bodies adorned with tattoos can be seen as masculine in particular groups whereas slim, toned bodies may be considered masculine in others; having a flair for poetry may be masculine for some sections while it is feminine for others. The differences and similarities between what is masculine and what is not within and across different socio-political sections are endless and constantly evolving.

Hegemonic Forms of Masculinities

As the name suggests, this category includes the traits that are predominantly considered ‘masculine’ in a particular society. A man who conducts himself in a manner that is expected of him as well as accepted by the society around him would fall in this category. For instance, some of the universal traits of hegemonic masculinity will be a man who is good at sports, has physical strength, is willing to protect the nation as well as its women, or is the sole bread earner of the house.

Marginalised Forms of Masculinities

In comparison to hegemonic masculinities, marginalised forms of masculinities consist of men who are in some shape or form barred from attaining the hegemonic state (Edley, 2017:45). This often includes disabled men or men who belong to a certain ethnicity, race, caste, or community that is a minority in a particular society.

Subordinate masculinities are those that “fly in the face of the hegemonic ideal” (Edley, 2017:45). Perhaps the most common form of subordinate masculinities is that of gay masculinities as it contravenes the hegemonic form— “The effete nature of gay masculinity also ‘offends’ the emphases found in the dominant ideal on the values of ruggedness and restricted emotionality (Edley, 2017:45).

The hegemonic state is not one that can be attained by all. However, that does not mean that it is not aspired by all. The aspiration to become the hegemonic male is perhaps what makes the complicit form of masculinity the state of a majority of men. “Most men pay homage to” the hegemonic ideal, thereby being complicit in their masculinity (Edley, 2017:45)

These categories allow us to view Hosseini’s male characters in a different light.

Amir constantly struggles as he tries to balance between the man that he is and the man that his father wishes him to be. Additionally, his constant comparison with Hassan, the illegitimate child of Amir’s father, sheds light on how men often have to change their personalities to fit into the mould of the man that they are expected to be. This book, via the means of different types of male characters and the type of masculinity that they choose to exert, allows the readers to analyse and identify the “subordinate, marginalised and complicit” (Edley, 2017:45) forms of masculinities that exist, co-exist, and are often looked down upon.

In The Kite Runner (Hosseini, 2003), we see Baba, and later on, Assef, who embody the hegemonic forms of masculinities. On the other hand, Amir, a boy who is lost in the world of stories, and art, and is not as out-going or ‘brave’ as his father would like him to be, is pushed to the marginalised form of masculinity, for he’s “barred from attaining the hegemonic state” of masculinity (Edley, 2017:45). Characters like Ali can be seen as falling in the category of complicit masculinity, for Ali accepts his position in the society as a poor, Hazara man who must serve his upper-caste employer and even comply in leading a life based on a lie, acting as Hassan’s father.

Over the course of the novel and the changing socio-political situation of Afghanistan, what constitutes hegemonic masculinity changes. Pre-invasion Afghanistan views the likes of Baba as a form of acceptable exertion of masculinity— an upper-caste, wealthy man who has travelled and acquired intelligence and intellect; is kind and philanthropic, yet assertive and bold when the situation demands him to be; as well as a man of morals and principles. He “had built the most beautiful house in the Wazir Akbar Khan district, a new and affluent neighbourhood in the northern part of Kabul”, letting his wealth speak for himself and asserting his dominance without him having to do anything (Hosseini, 2003). For he is a man and must not express his emotions, Baba is never able to accept that Hassan is indeed his son, and is ‘compelled’ to keep him as a servant’s son in the house. To compensate for his guilt, he builds an orphanage and bound by the clutches of society, caste and legitimacy/illegitimacy, he cannot accept his own son. As Nigel Edley (2017) cites in Men and Masculinity: The Basics, one of the purposes of a man’s body is to serve the Nation. Baba’s character fulfils this requirement of masculinity, for the move to America proves to be especially difficult for him. Whilst escaping Kabul, he is willing to sacrifice his own life in order to safeguard the ‘honour’ of a woman who gets targeted by a Russian soldier. Hence, Baba’s masculinity is one that also fulfils his duty to protect all women, not just his Nation.

Both his sons, Amir and Hassan, display an interplay of complicit and marginalised masculinity. Amir is the son who enjoys the social status and the respect that comes to him despite not having to work for it since he is the legitimate child. However, Hassan spends his life as a low-caste Hazara, living as the servant’s son, being unabashedly loyal to Hassan and Baba, yet never gaining any acceptance, socially or personally. Consequently, his life is filled with sorrow, tragedy, and turmoil; with him being sexually assaulted as a child by an upper-caste boy and ultimately killed for being a lower caste.

“I watched him fill his glass at the bar and wondered how much time would pass before we talked again the way we just had. Because the truth of it was, I always felt like Baba hated me a little. And why not? After all, I had killed his beloved wife, his beautiful princess, hadn’t I? The least I could have done was to have had the decency to have turned out a little more like him. But I hadn’t turned out like him. Not at all.”

(Hosseini, 2003)

References

- Ahmadi, B., & Stanikzai, R. (2018). Redefining Masculinity in Afghanistan. Retrieved 2 January 2022, from https://www.usip.org/publications/2018/02/redefining-masculinity-afghanistan

- Edley, N. (2017). Men and Masculinity: The Basics. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hosseini, K. (2003). The Kite Runner. New York: Riverhead Books.

Raj Nandini is a content and copywriter. She has completed her Masters in Gender Studies from Dr B. R. Ambedkar University, Delhi and her Masters in English Literature from Indira Gandhi National Open University. She is an avid consumer of cinema, literature as well as pop culture and is interested in writing about the same.