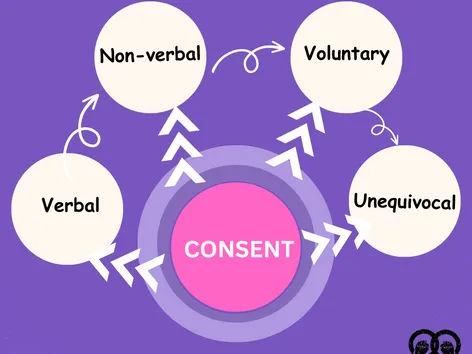

Rape is defined under section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) as a sexual act performed without the “consent” of the woman. Consent is defined under Explanation 2 of the Section as an “unequivocal”, “voluntary”, “verbal” or “non-verbal” communication by the woman to participate in the sexual act. This is the new affirmative standard of consent provided by the JS Verma Committee in 2013, in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya rape case. According to this definition, consent is actively sought and expressly communicated. Colloquially, it is the “yes means yes” rule, which aims to ensure greater sexual autonomy of individuals. However, it is also liable to certain qualifications. For instance, consent given in a state of intoxication; by a mentally unsound woman; obtained through threat or coercion of any sort; or by a female below the age of 18 will not be considered valid.

Credits: Aastha (Graphics Intern at Mandonna)

The new definition evolved post a severe national as well as international backlash. Hence, it was expected to be feminist and progressive in nature. While it does look hunky-dory on the face of it, it’s crucial to present an antithesis. A simple statistic will lay the record straight. The conviction rate in cases of crime against women in India stood at a measly 26.5% in 2021, down from 29.8% in 2020. While this obviously signals sluggish institutional and judicial practices, it also highlights the systemic insensitivity towards sexual assault victims. Indian society is notoriously patriarchal and misogynist in nature, and its democratic institutions also reflect these biases. However, besides the processual apathy, there are also definitional lapses that withhold the proper administration of justice to the victims of rape and sexual assault.

What makes consent contentious when it comes to its socio-legal definition? And what are the attributes within this new definition that have withheld the Indian rape provisions from being truly just? Here’s a critical look.

Rape laws in India are gender biased. The crime can exclusively be committed by a man on a woman. The distinction between sex and gender is also not very well understood by contemporary jurisprudence. Only a person in possession of a penis (or the male sexual organ) is capable of being accused of rape by a person in possession of a vagina (or the female sexual organ). This narrow definition of rape stems from the rigid and sexist definition of consent, where a man is legally incapable of consenting to a sexual act. The penile-penetration condition used in the Indian rape jurisprudence renders men (or those in possession of a penis) to always be considered as the perpetrator of rape and never the victim.

Legal experts have long regarded that it is biologically impossible for women to rape men, and that rape would hence be considered a gendered crime. This leads to a large number of gender identities being excluded from the sphere of justice when it comes to sexual assault. Gender identities, other than women, do get raped. However, men above the age of 18 and transgender persons who do not identify as women, have no remedy for sexual assault or rape under IPC. Neither section 375 nor the Vishakha guidelines for workplace harassment are gender inclusive. This is highly deplorable, as the sexual consent of each human being should be considered equal under Article 14 of the Constitution.

This is in direct contrast to many developed countries like the USA, Australia, Canada, Finland and Ireland, which have gender-neutral rape laws. Unfortunately, the laws of our country reflect the societal stigmas and biases when it comes to rape. It is not sensitive to the multitude of gender identities that inhabit India either.

As per section 375, consent given by an individual below the age of 18, will not be considered valid. This is because, as per legal definitions, such a person is classified as a minor or “child”. Hence even consensual intercourse between two minors would fall under the POCSO act and be liable for criminal proceedings. This makes consent contentious for adolescents (especially those above 15) who may be in consensual sexual or romantic relationships. The CJI has also highlighted difficulties in the trial and examination of cases involving consenting adolescents.

It should be noted that the age of consent has been increased by the government of India successively from 16 in the 1940s to 18 with the enactment of POCSO. This, however, is in direct contrast to most other countries where the age of consent is often set from 14 to 16. This includes European nations like Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, England and Wales, as well as Asian nations like Bangladesh, Japan, Sri Lanka. Statistics show that as development levels increase, more teens would be engaging in consensual sex. Making it liable to criminal proceedings would only encourage the misuse of the rape provisions by the parents to control their adolescent children.

However, this is an urban position to the issue. The Indian landscape is highly diverse, and the primary reason for pushing the age of consent to 18, was the increasing incidence of consummation of child marriages. The “age of consent” clause of IPC, brings child marriage victims under the ambit of justice when it comes to sexual exploitation during marriage. Hence, looking at the extremes in which Indian society operates, it’s vital that the courts exercise informed discretion as per the specific facts and circumstances of individual cases in order to administer justice effectively.

While the affirmative standard of consent in Indian jurisprudence allows for consent to be revocable at the convenience of the woman, it does not apply to married women. Sexual consent of married women is not considered relevant. The doctrine of marital exemption protects husbands from the prosecution regarding the rape of their wives because this doctrine is based on the belief that there is a general and permanent consent of the wife to sexual intercourse with her husband by implication of marriage. The doctrine is so deeply rooted in the Indian jurisprudence, that not only is marital rape obliterated from section 375, but even the sexual violence inflicted by a husband on his wife during legal separation, is liable for a considerably less punishment than sexual violence in any other circumstance.

The court judgements provide no respite, as various high court judgements regarding marital rape present a legal paradox. In 2018, the Gujarat High Court ruled that non-consensual intercourse by a husband was not rape. The same year, the Delhi High Court observed that both men and women had a right to say “no” and that marriage did not imply consent. The fact that the Supreme Court has conveniently looked away from the matter for years only provides legitimacy to the history of sexual violence and patriarchal exploitation of women in our country. The differing standard of consent for married and unmarried women respectively is also against the right to equality under Article 14 of the constitution.

As of 2019, marital rape has been criminalised by 150 countries. This long-standing issue regarding the punishability of marital rape is currently Sub-Judice under the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling is highly awaited, as it would decide the future course of married women and their right over their own bodies and sexuality.

Except when the accused may be in a position of authority or trust (as per Article 114 of the Indian Evidence Act), the burden of proving the rape remains on the prosecution. This is a major fallacy of the Indian judicial system, as it forces the victim to relive the trauma of sexual assault. It also amounts to systemic apathy which thwarts the victim from seeking justice.

To ensure, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the sexual intercourse took place without the consent of the woman, the judiciary employs a number of tests of extraneous circumstances. This includes a number of misogynistic and insensitive standards like the sexual lifestyle of the victim as well as the arbitrary distinction between a “modern” and a “traditional” woman. These labels are attributed undue weightage because they’re mistaken to be watertight and static concepts capable of determining the character of a woman. Other standards include the presence or absence of injuries; evidence of aggressive resistance; and post-assault behaviour.

Many cases have been disposed of using the extraneous circumstances test, where even though the sexual intercourse was proven, the claims of non-consent by the victim were not believed by the court, based on the extraneous circumstances. In the Mathura rape case, the victim’s sexual history and lack of bodily injuries were used to refute her claims of non-consent. Rape was overruled even when sexual intercourse was proven, which led to the acquittal of the perpetrators. Similarly in the Mehmood Farooqui case, the victim’s lack of violent resistance and history of prior romance with the perpetrator was used to acquit the accused.

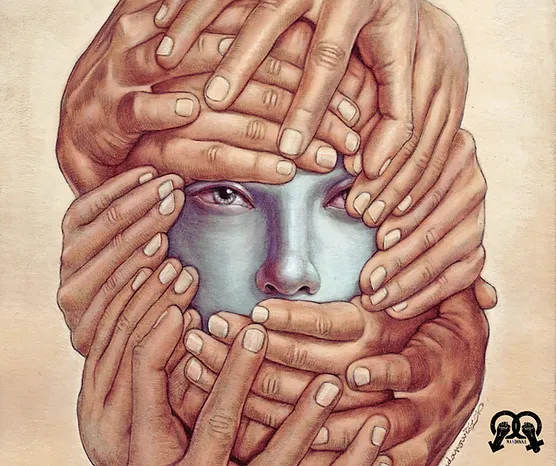

These standards overlook the delicate crevices that exist in a sexual assault case. Most rapists and sexual assaulters are known to the women. Besides a woman may not resist out of fear of her life, as most sexual assault cases end with the murders of the victims. Extraneous circumstances test remains on the most insensitive and inconsiderate practices of the judicial system, which thwarts the administration of justice to sexual assault victims.

The affirmative standard provides for no grey areas when it comes to consent. Simply put, it means that a woman always means “no”, unless she is expressly stating agreement. While it aims to challenge dominant (hetero) sexual scripts built upon forceful seduction, it has not yielded the desired results. It is susceptible to misuse, because of the processual and systemic lapses that plague the judiciary. Hence, in order to realise the full potential of this progressive standard, we need to address certain problems within our system.

Foremost, the judiciary and executive should be sensitised towards sexual assault cases. While there are a number of guidelines for the executives to ensure a smooth process of filing complaints, the judiciary provides a topsy, turvy path to justice. Hence appropriate training for judicial sensitisation and training in sexuality education could help establish appropriate and accommodative views towards the general public and sexual minorities in India. However, it has been noted that criminal law reforms remain largely ineffective because the members of the criminal justice machinery have their own convictions based on societal conditioning. Therefore, promoting affirmative consent as part of sex education in schools and colleges along with changes in criminal law, can go a long way in establishing the right attitude towards consent within young minds.

Existing notions of consent can be reformed to make it more gender inclusive and age appropriate. New models of consent like the consent-plus model, propounded by the UK feminist researchers could be tested in the Indian setting. As per this model, obtaining consent should not be a game to see which tactics can be used to get a “yes” but should rather simulate a mutually respectful and supportive environment so that it’s ensured that a sexual encounter is what both parties truly desire.

The judgement regarding marital rape and consent of married women is highly awaited, as it would determine the future course of action for the judiciary regarding implied marital consent. Similarly, PILs could be filed to elicit a greater judicial understanding regarding the age of consent, which has emerged to be a major cleavage in Indian society.

There is no denying that assessments of consent are riddled with issues. It is also evident from the various court judgements that unless there is a major change in the interpretation and framing of laws with respect to the elements of consent, it will be difficult to secure convictions in rape cases. It is in this context, that we need to ask ourselves as a society, how do we view sexual consent? And what can be the social and institutional implications of our views?