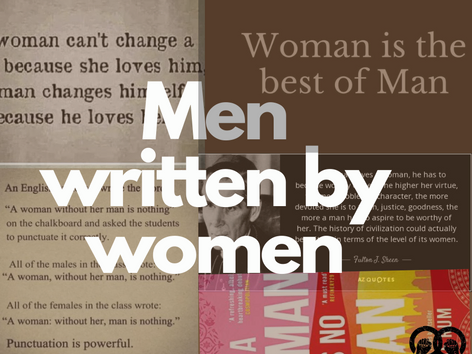

‘A man written by a woman’— if you’re even slightly acquainted with social media and the conversations that take place within these platforms, then you must’ve come across this statement at least once in your life.

Well, what is it about men who are supposedly written by women that the media, people, and pop culture itself are now redefining, conceiving, and idealising new ideas, moulds, and frameworks when it comes to describing masculinity?

Herein, women reclaim the gaze that has been so long set on their bodies and use it to highlight multiple aspects of their character, such as their vulnerabilities, sensibilities, flaws, and a vast array of other characteristics that exceed the narrow and constricting pathways of one’s physical appearance. One could say that the existence and prevalence of the female gaze is a direct subversion and attack on the male gaze; while the male gaze has objectified and marginalised women as mere playthings or showpieces within the context of visual representation and media, the female gaze has systematically deconstructed and dismantled this gaze by putting forth one of their own.

The female gaze puts forth the idea of a man that pervades and goes beyond the idea of a supposedly tough, aggressive, and unfeeling stoic who would only express emotions if the expression of the same led to the objectification of the female character; instead, it puts forth an extremely different version of a male character that is emotionally aware, respectful, loving, expressive, and reliable; he is not afraid of expressing his emotions and love; his masculinity isn’t threatened by the idea of a successful wife; and he sees his love interest as a person rather than a mere plaything.

The female gaze, instead of surrounding and basing its men on the pillars of conventional Heteropatriarchal ideas of masculinity, explores them as actual people, most importantly as subjects and not objects (Hercampus, 2021). Jim, portrayed by John Krasinski in the hit sitcom The Office, Dr Jehangir from the 2015 movie Dear Zindagi, Rana from the 2014 Bollywood movie Piku, and Sunny Gil from the 2015 Bollywood movie Dil Dhadakne Doh often stand and hold their forts as the poster boys for the trope of men being written by women. These men are portrayed as reliable, respectful, and attuned to their own as well as their partner’s emotions, a narrative that the erstwhile stoic representations of masculinity very much ignored.

To understand the female gaze, we must first understand and critically analyse the male gaze. What is the male gaze, one might ask? Laura Mulvey, a filmmaker and theorist, first coined the word male gaze in 1973. It is often deemed a response to the claims of scopophilia in movies. Scopophilia is the sexual pleasure derived from looking at someone; it is also interchangeably used with the term voyeurism. According to Mulvey, “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure… with [her] appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact.” Through this statement, Mulvey talks about how men have been rendered as the more active members of the world, the supposed ‘go-getters, while women have been rendered to a passive role in their own lives, merely existing for the pleasure and satisfaction of men; hence, movies are made by men for men, where women serve their roles as mere objects being sexualised within their roles for the pleasure of men within the story as well as the men outside of it (Studiobinder, 2021). So every time a camera pans out to show each and every inch of the leading lady’s body, you are seeing the male gaze being panned out on screen. Every time the hero decides to make a lewd remark about the female character’s appearance, you can see the male gaze being panned out on screen, and every single time the female lead is exposed to unnecessary objectification and nudity that the male characters are seemingly bereft of, you are seeing male gaze being played out on screen.

Prime examples of the male gaze could be seen in multiple movies, books, and media representations. The perfect quirky woman, whose hair always falls down in the perfect way and has the slimmest of waists but the most voluptuous of curves, is an ideation of the male gaze found within popular cultures and media. The idea of Megan Fox in the movie Transformers comes to mind when one talks about the manifestation of the male gaze. Megan Fox wearing provocative clothing whilst fixing a car while the camera rather obviously zooms in on every inch of her body was every man’s “cool girl” fantasy and their ‘manic pixie dream girl’ fantasy coming true on screen. What this resulted in though was stereotypes and archetypes created for women where even their own bodies and sexuality were catered towards the appetite of other men. It also left a long-lasting legacy wherein women now had to compete with unrealistic body standards, thereby being reduced to nothing but their physical appearance. Even if we look at male friendships and characterisation within the scope of the male gaze, we see that they are barely explored from a vulnerable and sympathetic perspective; they only have two moods, which alternate between being either sexual or aggressive. In terms of male camaraderie and relationships, the male gaze conveniently follows the trope of “boys being boys,” with conversations and interactions being limited to those of alcohol and woes caused by women.

Men as well as women are treated with sympathy and kindness, treated as wholes with flaws and quirks rather than parts of themselves. A prime example of the female gaze can be seen through the Zoya Akhtar directorial “Zindagi na milegi dobara,” where both the male and female characters had their vulnerabilities, challenges, and insecurities by highlighting the same the director and writer managed to claw their way out of the constricting frameworks that mainstream media had so conveniently designed for them. Imran, essayed by Farhan Akhtar, was not just comic relief; Arjun, essayed by Hrithik Roshan, was not an unfeeling robot; Arjun, essayed by Abhay Deol, was not a passive mediator; and the characters of Natasha and Laila, essayed by Katrina Kaif and Kalki Koechlin respectively, were not just pretty faces to look at. Even the conversations these characters indulged in, which included them discussing their fears, insecurities, and trauma, gave the audience a taste of all that never was but only could be when it came to characterising our male and female protagonists as not just objects but subjects.

Men written by women cater to not just the emotional needs and well-being of women but also present a rather thoughtful and articulate picture of Male characters being comfortable in their skin, their flaws, their emotions, and most importantly of all, their place in their partner’s life. So while women, through literature and popular media, had been conditioned to be the passive figures catering to the expectations and standards of men around them, the trope of “men being written by women” subverts this trope by creating female-centric spaces where women and their needs, emotions, and happiness are being catered to. It creates a space where the ideation of masculinity moves beyond the place of self-interest and self-indulgence to a place where masculinity is based on partnership, respect, and care. These men quite literally embrace both their male and female characteristics, while women are given centre stage, where they are explored in terms of their dreams, flaws, hopes, and aspirations and are not reduced to being one’s love interest. Hence, men written by women tread a tightrope where they navigate being emotionally and intellectually aware enough to match a woman’s intellectual sensibilities while also having traditionally masculine traits that can make a woman feel secure and taken care of in times of need. In the end, one could say that this new ideation of masculinity that manifests itself in the form of men written by women is a way for women to project their ideals and standards of a love that they crave onto fictional characters in order to subvert old expectations of love, partnership, and masculinity and in a bid to create new ones. While a common criticism of this ideation is that it creates unrealistic tropes and commodities that men would have to compete against,

I personally stand on the opposite side of the spectrum, wherein I believe that this trope facilitates the movement of the female perspective from a passive to an active role and articulates new and more sensitive ideas of expression and sensibilities pertaining to gender.