Understanding the Male Gaze

At its core, the male gaze theory posits that visual media is constructed from a heterosexual male perspective, with women being objectified and positioned as passive objects of desire. The male viewer assumes the role of the active spectator, while female characters are subjected to objectification and fragmentation. This objectification often manifests through the sexualization of women’s bodies, reducing them to mere visual pleasure for the male viewer.

Theorizing in India

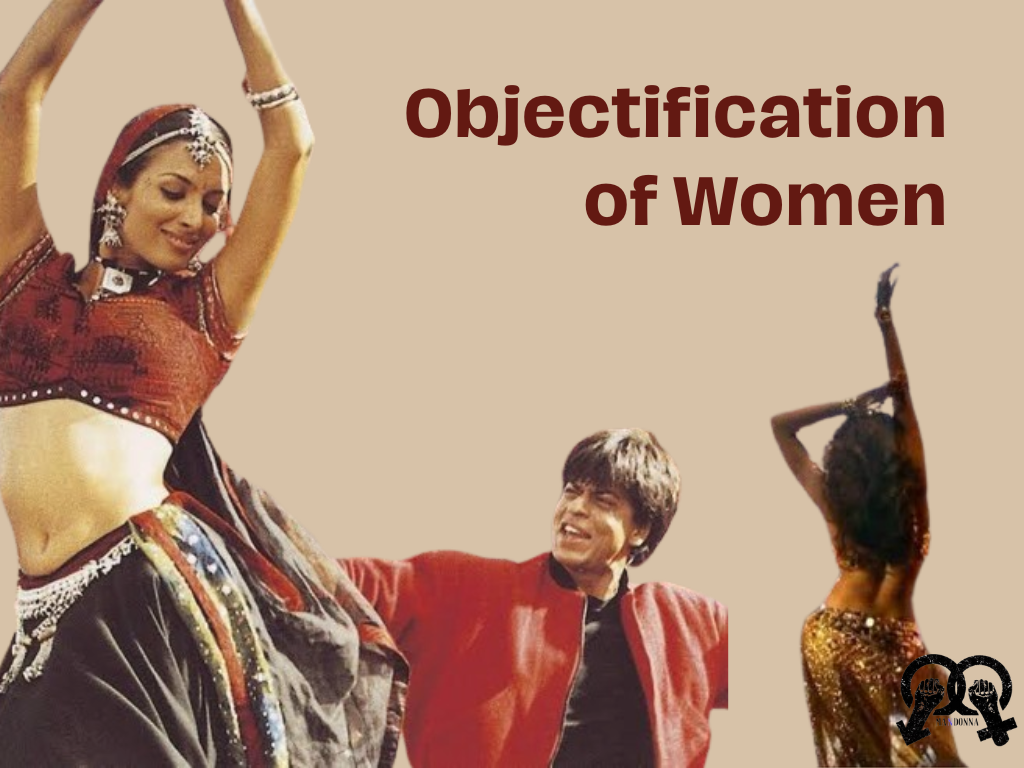

Historically, Indian cinema, often referred to as Bollywood, has been a dominant medium through which the male gaze is perpetuated. The objectification and sexualization of women in Indian cinema are evident through the emphasis on the female body, particularly in song and dance sequences be it Malaika in Chaiya Chaiya or Deepika in Lovely, the perception of talented and persevered women boil down their toned bodies and their skin, where women are often depicted as sexual objects for the male viewer’s consumption or establishing a thirst trap for their male counterparts. The camera angles, lighting, and visual composition frequently align with the male gaze, prioritizing the male perspective and desire. Moreover, the influence of the male gaze extends beyond cinema and pervades other forms of media in India. Advertising, television shows, and online content often reinforce and perpetuate gender stereotypes and objectification of women. The media industry, to a large extent, reflects and perpetuates societal norms, with male perspectives dominating the narratives and representations.

Credits: Sabia, Graphics Intern at Mandonna

However, it is important to note that the male gaze is not without criticism and resistance in India. Feminist scholars, activists, and filmmakers have been challenging the male gaze and advocating for more inclusive and diverse representations. There has been an emergence of alternative narratives and counter-cinemas that seek to subvert traditional gender norms and challenge the objectification of women and it is time we mainstream them.

The male gaze theory holds relevance in the Indian context, particularly within the realm of Indian cinema and media. While the male gaze continues to shape representations and gender dynamics, there are limited efforts to challenge and subvert its influence because of the entrenched needs of the viewers which tend to expose the inherent pleasure gained out sexual fetishization of women’s bodies. By promoting diverse narratives, amplifying marginalized voices, and fostering critical engagement, India should witness a shift towards more inclusive and equitable media representations that challenge the dominance of the male gaze.

Implications and Criticisms

The male gaze theory has faced its fair share of criticisms over the years. Some argue that it essentializes women’s experiences, disregarding the agency and diverse perspectives of female characters. Additionally, critics contend that the theory overlooks alternative gazes and fails to account for the influence of race, class, and other intersecting identities.

Contemporary Relevance and Adaptations

Despite the criticisms, the male gaze theory remains relevant in contemporary discussions of media representation. Scholars and activists have expanded the theory to include intersectional approaches, recognizing the importance of diverse perspectives and challenging the homogeneity of the male gaze. The theory’s influence has also extended beyond film studies, permeating disciplines such as advertising, photography, and digital media.

Implications and Future Directions

Recognizing the role of both media creators and consumers, it is essential to cultivate media literacy and critical analysis. By engaging with media content critically, individuals can challenge and subvert the male gaze, supporting more diverse narratives and alternative gazes. Additionally, fostering inclusivity and intersectionality in media creation can lead to greater representation and empowerment of marginalized groups.

References

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6-18.

Hollows, J. (2000). Feminism, femininity, and popular culture. Manchester University Press.

Tasker, Y. (1993). Spectacular bodies: Gender, genre and the action cinema. Routledge.

Radner, H., & Stringer, R. (Eds.). (2013). Feminism at the movies: Understanding gender in contemporary popular cinema. Routledge.

Hooks, B. (1992). Black looks: Race and representation. South End Press.

Doane, M. A. (1982). Film and the masquerade: Theorizing the female spectator. Screen, 23(3-4), 74-87.

Bruzzi, S. (1997). Undressing cinema: Clothing and identity in the movies. Routledge.

Articles:

Modleski, T. (1988). The terror of pleasure: The contemporary horror film and postmodern theory. Wide Angle, 10(3), 62-70.

Mulvey, L. (1981). Afterthoughts on “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema” inspired by Duel in the Sun. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, 15, 12-15.

Kaplan, E. A. (1994). Is the gaze male? Film and femininity. In E. Ann Kaplan (Ed.), Feminism and film (pp. 32-47). Oxford University Press.

Williams, L. (1991). Film bodies: Gender, genre, and excess. Film Quarterly, 44(4), 2-13.

Silverman, K. (1988). Dis-embodying the female voice. Critical Inquiry, 14(2), 289-311.

McSweeney, T. (2018). Feminism and film theory: The legacy of Laura Mulvey. In C. Grant & A. Bainbridge (Eds.), Feminism and the power of love: Interdisciplinary interventions (pp. 173-186). Routledge.

Authorship Credits

Kaushiki Ishwar (she/they) is a student at Miranda House pursuing History and Philosophy. Her research interests include feminist epistemology and its intersection with neoliberal cybernetic superstructures. Her favourite philosophers are Zizek, Gayatri Spivak, Judith Butler and Baudrillard.