In 2021, 428,278 of the six million crimes recorded in India involved crimes against women. Noticing an increase in gendered crimes, the Indian government sanctioned INR 2,919.55 crore (approximately USD 360 million) in 2019 under the ‘Safe City Project’ to deploy face recognition-enabled CCTV cameras and drones in eight cities to provide “safety to women in public places”. This involved the ‘Smart Cities Mission’ in 100 cities in 2015, with a budget of INR 191,294 crore (about USD 25 billion), which would construct smart cities with similar surveillance infrastructure.

Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets, a comprehensive study by Shilpa Khan criticises gendered safety measures that restrict women’s movement through surveillance. This begs the question of where investment is most needed to actualize women’s public safety in urban cities. In other words, what would a feminist smart city look like and how would it differ from surveillance-driven infrastructure? During my research for urban studies, I found a few lucrative plans that facilitate gender-based town planning. For example, some goals of the LCAU seed grant are:

(1) to gather perspectives from social workers, women’s rights organisations, and gender minorities in India on which specific areas of capital should be allocated to create safer public spaces for women in urban India.

(2) To use this data to create a public-facing digital visualisation map which looks like a measure to stop crimes in spaces which are badly lit and not under the radar of town planning because of its residual nature and website highlighting and amplifying community voices; and

(3) To assist in organising the participating grassroots communities to use these outputs to influence policy and integrate a more democratic process into smart city projects addressing safety and mobility.

While urban planning and design strategies frequently urge for better street lighting, mixed-use development, and more eyes on the street, there is also a need to understand how perceptions of safety are cognitively, sociologically, and geographically created.

Critical Assessment through South Asian-Centric Literature

As argued in Why Loiter: Women and Risk on Mumbai’s Streets by Shilpa Khan, the demand for safer public spaces for women must not be met by excluding other minority groups, whether migrants, particularly working-class women and lower castes, and/or Muslim men and women in Indian cities, or by patriarchal surveillance of women’s bodies and actions.

Similarly, rather than viewing the city as a threat from which women must be protected, we must see and design public spaces in which women would like to spend time, or “loiter,” or “to not have a purpose to enjoy public spaces, use public infrastructure after dark, or indulge in consensual flirtation and sexual encounters”.

As a result, a project to make a city safer for women is concerned not just with physical changes but also with the right of women to loiter without eliminating other minority identities. This necessitates additional research into what motivates women of various income levels, castes, religions, and regions to spend time in public areas, as well as what kind of eyes on the street encourage women’s presence in public spaces.

Walking out of a metro station in Bengaluru and Delhi and seeing expanses of ‘smart’ bikes and cycles is a typical sight. However, these cycles are only accessible via a smartphone application and are not well adapted to the city’s automobile-clogged major roads or the city’s inadequately illuminated, poorly maintained, pothole-ridden alleys and by-lanes. In addition to this, it does not take into consideration the gendered dimension of bicycle use such as road safety, street harassment or clothing worn by the majority of women, which makes it discriminatory.

So while it is important to consider sustainable urban mobility policies that emphasise non-motorized transportation infrastructure, such as provision for pedestrians and bicycles, and an emphasis on low-cost public transportation, notably bus transportation, they must also incorporate a feminist perspective. This is all the more important for women. According to research in 2015, women in the city rely on walking at a higher rate than men. Women, in addition to walking, are heavily reliant on public transportation. Even when a household’s income increased, men began to use private vehicles, but women continued to use public or paratransit forms of transportation. This suggests that women are already the dominant consumers of non-motorized modes of transportation such as walking and are heavily reliant on public transportation networks, particularly bus services. This necessitates long-term mobility strategies that balance planning with safety, convenience, and comfort for women and girls.

What is sustainable mobility for Women and Gender Minorities?

Sustainable mobility for women refers to transportation systems and practices that prioritise the safety, accessibility, and convenience of women while minimising environmental impact. This concept recognizes that women often have unique mobility needs and challenges compared to men, including concerns about personal safety, caregiving responsibilities, and limited access to transportation options. This can include well-lit and secure public transportation stops, gender-sensitive urban planning that considers childcare facilities and healthcare access, as well as affordable and reliable transportation options that cater to various schedules and destinations. Sustainable mobility for women involves engaging women in the planning and design of transportation systems. It also entails raising awareness about the importance of gender-responsive mobility solutions and fostering a cultural shift towards a more gender-inclusive approach to transportation.

Hence, The issues in planning sustainable urban mobility that rely on NMT are multifaceted. To begin, transportation planning appears to be distributed across various, siloed departments, with no interaction with the city’s overall urban planning procedures. Second, within urban transport planning, NMT planning has been generally disregarded or given only lip respect. Third, there appears to be a complete dearth of a feminist approach in thinking about mobility design and planning that includes girls, women, and gender minorities.

Why do we need a feminist perspective on urban transportation planning?

Feminists have long emphasised how patriarchal gender roles cause women to be disproportionately burdened with unpaid household duties and care work, even if they work outside the home. A person’s social roles have a major impact on differences in trip purpose, trip distance, transportation mode, and other characteristics of travel behaviour, time of travel, and destination disparities.

In India, women’s use of public space is characterised by complex trip-chaining, which is defined as a series of short trips linked together between main or primary destinations, such as a trip in which a woman leaves home, stops to drop a child at a daycare centre, stops for grocery shopping, and then heads to her workplace or returns home.

Critically, what policy changes look like, understanding the usage of urban space and activities done in this environment will be dependent on the everyday life experiences of city dwellers, and it becomes critical to investigate how these places respond to the everyday needs of people, particularly girls and women. This is why Feminist Urban Planning, an approach to urban development that takes into account the concerns of many socioeconomic groups, is so important.

A Feminist Approach to Mobility Planning

Govind Gopakumar, Assistant Professor in the Centre for Engineering in Society (CES) at Concordia University, discusses the phenomenon of an automobility being constructed in the city that caters to the mobility demands of the wealthy elites while simultaneously marginalising the mobility needs of the rest. This has serious consequences for the movement of girls, women, and gender minorities, resulting in their exclusion from the metropolis.

A feminist approach to mobility infrastructure prioritises non-motorized transport (NMT) infrastructure such as pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, as well as the promotion of free or low-cost public transportation, particularly quality bus transportation with adequate frequency, connectivity, and well-maintained and designed bus stops. The plan of the Government of New Delhi to make all public transport free for women and girls on request is an excellent example of such a program. This encourages women and girls to use public transport, making these venues safer and more accessible to them, allowing them to be more autonomous. Similarly, it encourages the use of low-carbon public transit over private vehicle use.

Women’s experiences of cities in India continue to differ greatly from those of men; a lack of fair infrastructure limits their capacity to move around and engage freely in the city. Even the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, adopted in 2015, include a demand to make cities more inclusive, safe, and resilient, with an emphasis on women and girls in particular.

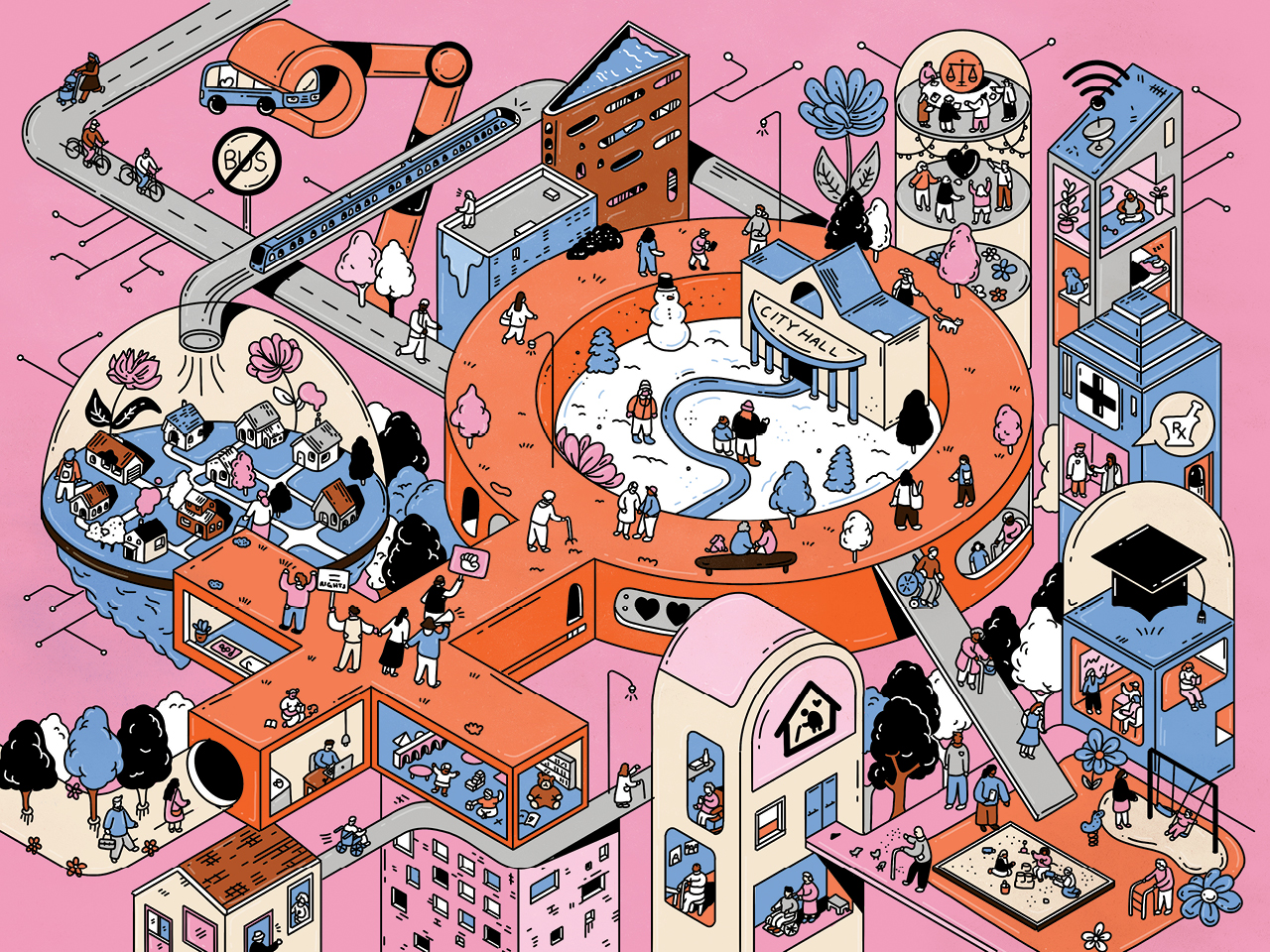

According to a 2019 study, Indian cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru are among the world’s least inclusive and fair. Vidhi’s (Legal Centre) ongoing research examines cities from a feminist viewpoint in order to ensure that Bengaluru’s urban planning and public spaces are attentive to the demands of women. What an ‘equitable’ city should have;

- Physical Infrastructure: streets that are well-lit, pathways, free public bathrooms that are open 24 hours a day, parks, and benches.

- Community housing, refugee homes, public child-care facilities, and skill development centres are examples of social infrastructure.

- Mobility Infrastructure: Free or low-cost public transportation, notably high-quality bus service with enough regularity and connectivity, as well as well-maintained bus stops.

- Public hospitals and reproductive health facilities, mental health facilities, legal assistance centres, and one-stop crisis centres are examples of institutional infrastructure.

How can cities be truly welcoming?

Legal and policy interventions could help establish more egalitarian cities. Gender-inclusive processes must be initiated first. This is far from the case in cities such as Bengaluru.

In Bengaluru, the mandate for urban planning is held by the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA), a parastatal institution with no people’s representation, let alone women being consciously involved in the process. Municipal laws must be updated to incorporate participatory planning and design processes that respect women and girls as empowered partners with shared decision-making power. A good example is the Catalan Neighbourhood Law, which was passed in 2004. The integration of a gender perspective in the design of urban places and facilities is required, with funding for projects under the law reliant on including gender equality, among other things.

Conclusion: Is ‘Feminist Urbanism’ possible?

Feminist town planning can encompass various aspects, including

- Safety: It focuses on creating urban environments that prioritise women’s safety by improving street lighting, enhancing public transportation access, and designing public spaces that discourage harassment and violence.

- Accessibility: Feminist town planning considers the needs of women, who often have different mobility patterns due to caregiving responsibilities. This can involve designing neighbourhoods that are walkable and easily accessible to essential services like schools, healthcare facilities, and childcare centres.

- Community Engagement: It encourages the active participation of women and other marginalised groups in the urban planning process, ensuring that their voices are heard in decision-making and that their specific needs are taken into account.

- Affordable Housing: Feminist town planning addresses housing affordability and housing options that accommodate diverse family structures, recognizing that women may have different housing needs than men.

- Economic Opportunities: It seeks to create urban environments that provide equal economic opportunities for women, including access to jobs and entrepreneurship.

- Green and Sustainable Urbanism: Feminist town planning often aligns with sustainable and eco-friendly urbanism, as it recognizes that women, especially in lower-income communities, are often more vulnerable to the negative impacts of environmental degradation.

The concept of ‘Feminist Urbanism,’ which focuses on developing equitable cities by allocating resources and services fairly to diverse social groups, particularly women and sexual minorities, is a useful tool for urban planning. It argues for creating streets and public places that encourage women to occupy the city, as well as designing services that meet the needs of women, transgender, and gender-queer people. These methods and techniques could go a long way towards realising women’s right to cities and providing equal opportunities for them.

References

Amin, A. (2014) Lively Infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society 31.7–8, 137–61.

Anand, N., Gupta, A. and Appel, H. eds. (2018) The Promise of Infrastructure. Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

Anand, N., Gupta, A., Appel, H. (2018) The Promise of Infrastructure. Duke University Press.

Appel, H. (2018) Infrastructural Time. In Anand, N., A. Gupta and H. Appel (eds.), The Promise of Infrastructure. Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

Arora, D. (2015) Gender Differences in Time-Poverty in Rural Mozambique. Review of Social Economy 73.2, 196–221.

Beebeejaun, Y. (2017) Gender, urban space, and the right to everyday life. Journal of Urban Affairs 39.3, 323–34.

Devika, J. (2008) Being “in-translation” in a post-colony: Translating feminism in Kerala State, India. Translation Studies 1.2, 182–96.

Devika, J. (2016) Aspects of Socio Economic Exclusion in Kerala, India: Reflections from an Urban Slum. Critical Asian Studies 48.2, 193–214.

Easterling, K. (2016) Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. Verso, London.

Elson, D. (2017) Recognize, Reduce, and Redistribute Unpaid Care Work: How to Close the Gender Gap. New Labor Forum 26.2, 52–61.

Ferguson, J. (2010) The Uses of Neoliberalism. Antipode 41, 166–84.

Flanagan. M. A. (2019) Constructing the patriarchal city: Gender and the built environment of London, Dublin, Toronto, and Chicago, 1870s into the 1940s Philadelphia: Temple University Press

Fredericks, R. (2014) Vital Infrastructures of Trash in Dakar. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 34.3, 532–48.

Hume, M. (2009) Researching the gendered silences of violence in El Salvador. IDS Bulletin, 40(3): 78-85.

Gupte, J. and El Shafie, H. (2016) The Dialectics of Urban Form and Violence. IDS. Jacobs, J. (1961) The death and life of great American cities.

Jayne, M. and Valentine, G. (2016) Alcohol-related violence and disorder: New critical perspectives. Progress in Human Geography 40.1, 67–87

Viswanath, K. and Basu, A. (2015) SafetiPin: an innovative mobile app to collect data on women’s safety in Indian cities. Gender & Development 23.1, 45–60.

Whitzman, C. (2007) Stuck at the front door: gender, fear of crime and the challenge of creating safer space. Environment and Planning A 39, 2715–2732.

Williams, G., Devika, J. and Aandahl, G. (2015) Making space for women in urban governance? Leadership and claims-making in a Kerala slum. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47.5, 1113–31.

Authorship Credits

Kaushiki Ishwar (she/they) is a student at Miranda House pursuing History and Philosophy. Her research interests include feminist epistemology and its intersection with neoliberal cybernetic superstructures. Her favourite philosophers are Zizek, Gayatri Spivak, Judith Butler and Baudrillard.