Learning Outcomes:

- To understand how anger as an emotion is subject to gender constructs and perceived differently between men and women.

- To examine how this reflects in the portrayal of women’s rage on screen and precisely what makes it subversive from patriarchal norms.

- To question the aptness and utility of ‘female rage’ both in cinema and real-life feminist discourse.

Introduction

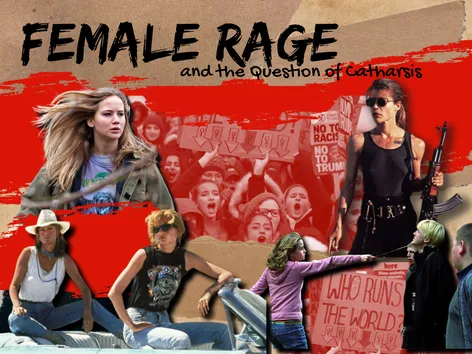

This explicit depiction of women’s anger on screen is perhaps par for the course with the rise in the number of films directed by women, nearly doubling from 9% in 1998 to 18% in 2022, according to a study published by the Centre for the Study of Women in Television and Film, San Diego State University. This promising, albeit far-below-the-mark trend has resulted in female characters being treated with much-deserved nuance and complexity, which in turn has led to their more realistic portrayal. Breaking free from the objectification and sexualisation by and for male audiences, the modern female character does not express her anger to indulge in some revenge fantasy trope that ultimately centres male violence and voyeuristic brutality, but to express her frustrations with the patriarchal system that has silenced her for so long. In this context, anger is a fundamentally gendered emotion. Female rage, by extension, is inseparable from the function of catharsis it plays for certain genders under patriarchy.

Gendering Anger as a Perceived Emotion

Legitimizing Characters’ Anger on Screen

Miriam Balanescu has provided a stellar and thorough examination in this regard as she traces the cinematic depiction of women’s anger, specifically of the violent kind, from film noir’s femme fatales to female heroines whose anger is legitimised as “sexualised, hyper-personal revenge in response to rape or loss of a child”. In an interview with Dr. Lisa Coulthard, professor of film studies at the University of British Columbia, the latter reveals how films such as Kill Bill (2003) thus “feminise” violence so as to align it with “stereotyped notions of female purity, emotionalism and ties to child-rearing”. In other cases, such as the 1970s horror slasher genre, female anger is legitimised yet again within the confines of patriarchy by ensuring that in films such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Halloween (1978), and Scream (1999), it is the “virginal and virtuous” woman who emerges as the sole survivor, while her friends “are punished with death for their sexuality” (Balanescu 2022).

This iconic ‘cool girl monologue,’ which has secured a definite place within the female rage arsenal on social media over the years, continues to reveal one of the most common manifestations of women’s anger in film and society.

Articulating Anger in Feminist Discourse

References

- Balanescu, Miriam. 2022. Female rage: The brutal new icons of film and TV. 10 12. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20221011-female-rage-the-brutal-new-icons-of-film-and-tv.

- Cappelle, Alice. 2023. Why female rage is here to stay. 01 24. https://youtu.be/q7Vh9nDNBi0.

- Chemaly, Soraya. 2019. How women and minorities are claiming their right to rage. 05 11. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/may/11/women-and-minorities-claiming-right-to-rage.

- Choudhury, Aradhana. 2022. Women’s Anger On Screen: Looking At Female Rage Through The Female Gaze. 06 28. https://feminisminindia.com/2022/06/28/womens-anger-on-screen-female-rage-through-the-female-gaze/.

- Devlin, Hannah. 2019. Science of anger: how gender, age and personality shape this emotion. 05 12. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/may/12/science-of-anger-gender-age-personality.

- Martin, Ryan. 2021. Are Men Angrier Than Women? 06 10. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/all-the-rage/202106/are-men-angrier-women.

- The Express Tribune. 2023. Ranbir Doesn’t Like It If I Raise My Voice: Alia Bhatt on Husband’s Temperament. May 9. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2415814/ranbir-doesnt-like-it-if-i-raise-my-voice-above-this-decibel-alia-bhatt-on-husbands-temperament.

- Srinivasan, Amia. 2017. “The Aptness of Anger.” Journal of Political Philosophy.

- Suman. 2016. “Anger Expression: A Study on Gender Differences.” The International Journal of Indian Psychology Volume 3, Issue 4.

Sanika is a second-year undergraduate majoring in political science at Miranda House, University of Delhi. An intersectional feminist, she’s passionate about media, politics, gender and social advocacy. Prone to ranting about her interests, she’s also a certified film-bro and part-time student journalist.

Editing Credits

Pavani is a third-year student of political science at Lady Shri Ram College for Women. Her areas of interest include peace and conflict, gender, and foreign policy. Being an editor at Mandonna allows her to expand her horizons, dig deep into the intersection of politics and gender, and have fruitful conversations with people on diverse issues.