Research Questions-

● What is the Mughal harem and what were the gender dynamics within the harem?

● How can the components of the “Myth of Oriental Harem” be defined?

● Within this myth how did the European Travellers view Eunuchs?

● Did Khwajasaras hold any power within the harem?

● Can we find a link between the study of the Mughal harem and the feminist discourse?

Introduction

The Mughal harem, a captivating and enigmatic institution, has long been a subject of fascination, curiosity, and imagination of scholars and the public for centuries. Yet, this fascination is often blotted by myths and misconceptions perpetuated through the Eurocentric lens.

Our intellectual endeavour to illuminate the subtleties hidden inside the Mughal harem is founded on a series of rigorous and probing inquiries. These questions serve as guiding beacons, directing our multifaceted investigation towards a deeper understanding of the following aspects: the intricate gender dynamics that shaped life within the harem’s cloistered confines, the enduring elements that comprise the “Myth of Oriental Harem,” European travellers’ perceptions of the enigmatic eunuchs who inhabited this realm, the wielded political power by the Khwajasaras within or outside the harem’s premises.

The Mughal Harem: An Introduction and the “Oriental Myth”

The Mughal harem, also known as the Imperial Harem was an important and complex institution within the Mughal Empire of India. The term “Harem” or “Haram” is of Arabic origin, signifying a sacred or forbidden place. In Turkish, it is referred to as “Seraglio,” while in Persian, the term “Zenana” is used. Mughal sources variously mention the Harem as “Harem Sarah,” “Haremgah,” “Zenana,” and “Raniwas.” Abu’l Fazl, the author of the Akbarnama also used the term “Sabistan-i-Iqbal,” (harem of fortune) which was the official designation for the Harem.

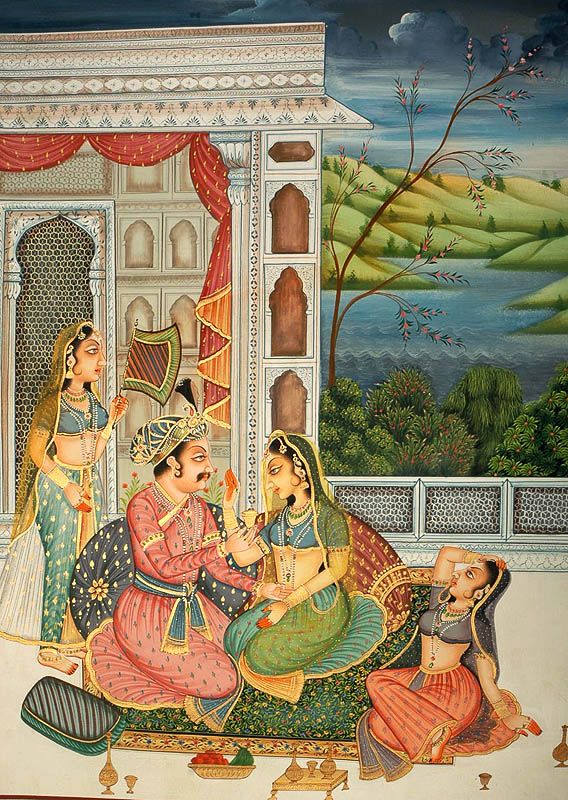

Credits: Pinterest

The harem complex was designed with imposing walls to preserve the tradition of the purdah and included several buildings, Its design incorporated a series of annexes that were created to create a sense of openness and comfort, including a central courtyard where communal celebrations took place. Within the complex, there were features such as fountains, ponds, and gardens. Access to the harem was restricted to a single entrance door, which was strictly guarded and regulated.

The primary residents of the harem were the female members of the Emperor’s family, encompassing his wives, mothers, stepmothers, foster mothers, sisters, daughters, and cousins. However, the composition of the harem has been a topic of debate among scholars. According to contemporary records, the Mughal Harem housed a huge number of women. The major source of knowledge is from tales written by European travellers, who were frequently affected by imaginations and rumours. Their portrayals of the harem are sometimes exaggerated, owing to their lack of access to the Harem’s inner workings. Some details can be found in the biographies of Jahangir and Babur. The Harem’s most thorough details can be found in Gulbadan Begum’s Humayun Namah. This literature, however, only covers the reigns of Babur, Humayun, and the early years of Akbar. Nonetheless, historians like Ruby Lal and K.S. Lal have used this literature extensively in their studies of Mughal women.

In her work “Historicizing the Harem: The Challenge of a Princess’s Memoir,” Ruby Lal discusses how the Mughal harem was frequently portrayed as a sexually charged, secretive, and exclusively feminine place. It is crucial to note, however, that this representation did not include the old or the sick. The harem was primarily built on the simple idea of delivering physical pleasure, which was thought to rule the private lives of both royal women and men.

She emphasizes several works that contribute to the recurring notion of the Mughal harem as a particular site. For example, in the New Cambridge History of India, John F. Richards reproduces the image of the harem as a “retreat of grace, beauty, and order designed to refresh the males of the households”. The same idea is again reflected in R. Nath’s work, Private Life of Mughals (1994) where he depicts Jahangir as an individual “immersed” in wine and women.

This pattern of description demonstrates a continued interest in linking the Mughal harem with the pleasures of both men and women inside the imperial spaces of the Mughal empire.

Another set of sources that describes the Mughal harem, and is often characterised by fascination, and rumours is that of the European travellers. Their efforts to understand this institution often led to the creation of fantastical narratives that bore little resemblance to reality. However, when examining the various accounts written by them, one needs to keep in mind the supposed challenges or limitations, the European travellers faced. One, of course, was their access to limited resources to comprehend the language and the culture of the locals. The second was they were barred from entering the private threshold of the imperial setting. One notable consequence of this cultural disconnect was the development of the “Oriental harem” concept. This construct was not based on empirical evidence but rather on a sensational amalgamation of bazaar rumours, isolated fragments of information, and sexual fantasies. The resulting narrative painted a picture of the Mughal harem that was lurid and occasionally fanatical. It is important to

emphasize that this portrayal was not limited to European audiences but also infiltrated the Indian consciousness, perpetuating stereotypes that persisted for generations.

Credits: Pinterest

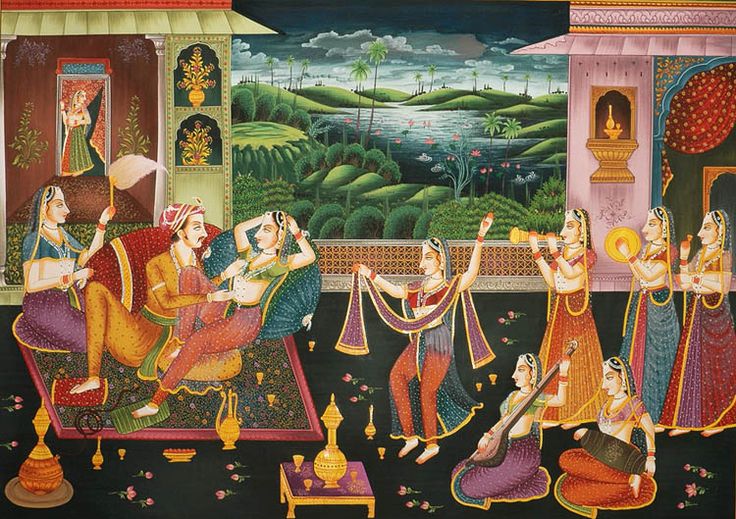

Travellers often had vivid imaginations about the number of women living there with varying estimates given. According to Niccolo Manucci, an Italian traveller, there were usually over two thousand ladies of diverse backgrounds within the mahal. Another English traveller, Thomas Coryat, said that Emperor Jahangir had a harem of a thousand women only for himself.

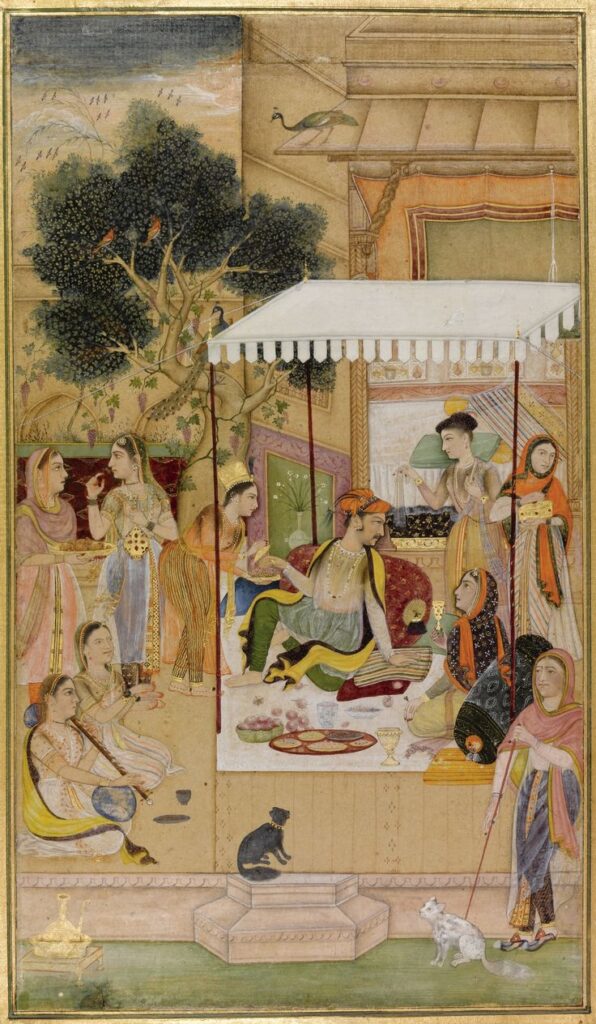

As for the physicians, there were unique protocols for entering the harem, – as noted by some travellers, with only the emperor having unrestricted access. Except for physicians, who had to be masked and discreetly guided, royal princes nearing puberty were not permitted in. Manucci, an Italian adventurer, recalled instances in which physicians were introduced to patients, sometimes leading to personal meetings. Various techniques of diagnosis were tried, including sniffing handkerchiefs and immersing them in water. The experience of English surgeon Fryer within the harem was humdrum, debunking sensationalised preconceptions.

The most common depiction of the “Oriental harem” portrayed the Mughal emperor as a cruel and despotic figure, ensconced within the harem’s confines and surrounded by a multitude of nubile young women. These women were often depicted as competing for the emperor’s attention while languishing in sexual frustration due to their limited freedom. This portrayal not only misrepresented the lives of Mughal women but also reinforced the notion that they led restricted and unfulfilled lives within a confined sphere of influence.

What were the actual characteristics and functions of the Mughal harem?

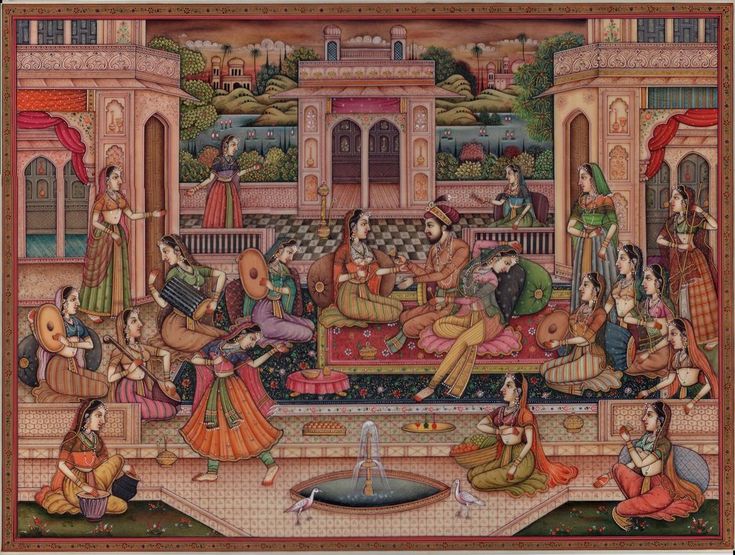

The Mughal harem was a complex organisation that included more than just the emperor’s consorts. It provided housing for female relatives, servants, artists, and bureaucrats in addition to royal wives and concubines, all of whom contributed to the complex web of activity there. These women took on significant roles, administering the home, supervising activities in the arts and culture, and occasionally getting involved in politics.

Purdah, the harem custom of isolation, is frequently misinterpreted. Although modesty and privacy were protected, it did not imply total seclusion. The zenana, as it was called, was a well-run environment where women were aware of their duties. Timurid females who were

educated had a thorough education in topics like mathematics, history, science, poetry, and astronomy since intelligence and success were respected.

Credits: Pinterest

The Mughal harem held economic sway. Some women actively oversaw its financial affairs, safeguarding the welfare of its citizens and assisting artists and craftspeople. To support the Mughal economy, royal ladies even engaged in trading. Throughout many reigns, the harem’s political power changed, although certain women served as counsellors, middlemen, and power brokers at the imperial court. The extent of their participation was determined by their connections to the emperor and their skill levels.

Contrary to impressions of total seclusion, the Mughal harem promoted communication between its female inmates and male authorities, ambassadors, and foreign tourists. Women frequently served crucial diplomatic roles that allowed information to flow and influence to be exerted between the harem and the larger court. These women made significant contributions to the cultural, social, and political realms because they had unique identities, aspirations, and agency.

Eunuchs in the Mughal Harem

The term “eunuch” is used in a variety of contexts throughout South Asia. It can include both castrated males and those who identify as “hijras.” The latter phrase has diverse meanings and might apply to intersex or transgender groups. However, this article focuses on the first category of eunuchs, who also known as Khwajasaras (master of the house) in the Mughal context, played a distinctive and multifaceted role within the Mughal harem. They occupied a unique position in the gender dynamics of the harem, and their presence and influence were a subject of curiosity and intrigue for European travellers and scholars alike.

While eunuchs, for the longest time have been associated with the household, in reality, their role extended beyond the threshold of the household. Scholars of slavery in South Asia as well as comparitive texts have noted the various positions held by these Khwajasaras outside the Mughal harem.

Credits: Pinterest

Scholars’ interpretations of the harem’s primary goal are inextricably linked to discussions about the function of eunuchs inside the Mughal harem. The harem is largely seen in most of the current studies as a mechanism for establishing dominance and control. In this setting, eunuchs are frequently portrayed as enforcers of authority over women and as guards of the male head of the household’s exclusive sexual privileges. For example, Kidwai contends that eunuchs played a crucial role in preserving a delicate balance between the sexes by guaranteeing a man’s uncontested power over the women under his control without jeopardising his sexual supremacy. Misra emphasises the serious repercussions that would follow if eunuchs failed to keep males other than the wives’ husbands from viewing harem inmates. Mukherjee emphasises the mistrust that people have of female guests by stating that only a few female relatives are allowed entry to the harem’s rigorous confinement. Collectively, these studies depict the harem as being strictly supervised by eunuchs, maintaining and limiting men’s total power, especially over sexual access.

Existing literature indicates that women who lived in the Mughal harem had some agency and that eunuchs were known to provide them with a variety of services. However, rather than having greater economic or political importance, this help is frequently perceived as being of a personal character. Lal, for instance, claims that eunuchs help harem ladies obtain alcohol or narcotics, while Mukherjee highlights their role in bringing males into the harem for covert gatherings. Such narratives frequently rely on sensational publications by outsiders like Bernier and Manucci, presenting the female inhabitants of the harem as holding power solely when they utilise eunuchs to obtain forbidden objects and people for private, non-political, and perhaps sensuous ends.

The literature on the Mughal harem highlights the contradiction between the imprisonment of aristocratic women and their political and economic importance. This calls into doubt whether these facets existed together or apart. The concept of separate public and private realms is contested by Ruby Lal’s study, especially during the early Mughal period. She contends that as the harem tightened its control over royal ladies over time, they were reduced to a status of “sacred incarceration” and lost their autonomy.

Eunuchs: Identity of Gender and Political Power

The gender identification of eunuchs is a difficult and subtle subject in the context of the Mughal Empire. Castration and its physical repercussions have affected ideas of eunuch bodies, according to recent studies. Eunuchs were typically castrated as children, before puberty, resulting in a lack of facial hair and an unbroken voice. These physical characteristics distinguish eunuchs from non-castrated men.

Credits: Pinterest

Scholars have proposed numerous explanations for how eunuchs were viewed in terms of gender. Some have labelled them as having an “indeterminate” gender or being in an “arrested male gender” condition. It is crucial to note, however, that Mughal eunuchs are identified as male, chiefly by their job titles and names.

Their gender identity may be deduced from the roles they held, which were not overtly feminine, as well as the names or titles they were given, which were frequently shared with non-eunuch males. This discovery calls into question the Mughal idea of a dichotomy between male and female genders.

Furthermore, while eunuch bodies differed from non-castrated men’s, they were not considered outcasts. Instead, they were seen as normative characters inside affluent houses, and their physical characteristics were occasionally praised.

Thus, the intersection of gender identity, physicality, and societal perceptions of eunuchs is a complex area that merits further exploration in the historical context of the Mughal harem, and becomes important when examining eunuchs as the “mid-rung of power”.

Eunuchs in the Mughal Empire occupied a unique and influential position within the political hierarchy, serving as a mid-rung of authority. This role became particularly evident during Emperor Akbar’s reign, as exemplified by notable eunuch officers like Itimad Khan, Khwaja Khas Malik, and Khwaja Daulat.

Itimad Khan: Itimad Khan held a prominent and vital role during Akbar’s rule. He was entrusted with the crucial task of managing the state’s finances, a position of significant responsibility. What made his appointment remarkable was that he was a eunuch, chosen for his loyalty and financial acumen. Later in his career, he was appointed as the governor of Bhakkar, showcasing the trust placed in eunuchs for important state functions.

Khwaja Khas Malik: He received the distinguished title of “Ikhlas Khan” and held a high rank within the Mughal court. This elevation in rank underscores that eunuchs could rise to influential positions within the empire based on their proximity to the emperor and their dedication to their roles.

Khwaja Daulat: Khwaja Daulat’s career began in Mughal service under Khan-i-Zaman, a Mughal noble. He ascended to become the chief of eunuchs, holding the title “Naziruddaula.” His influence extended beyond his official duties, with one of his eunuchs managing various

aspects of his affairs. This exemplifies how eunuch officers held not only official roles but also personal influence.

These eunuch officers maintained a distinctive and distinct status within the Mughal court, defined by their proximity to the emperor and intimate access to the harem. They were given significant tasks, such as handling funds and monitoring different elements of government. Their devotion was appreciated, and their absence of familial ties made them dependable. Eunuchs were allowed to collect significant riches and were involved in construction operations, which increased their reputation.

Eunuchs progressively retreated from the interiors of the harem as the Mughal Empire grew, and their functions transformed. Female guards took on additional responsibility within the harem, while eunuchs patrolled the grounds outside the enclosures. Although their roles changed, their historical relevance in Mughal politics as a mid-rung of authority remained an important component of the empire’s government.

The study of eunuchs in the Mughal Empire, in essence, emphasises the delicate interplay between gender identity, physicality, and cultural attitudes. It also emphasises the significance of eunuchs as crucial players in the empire’s political landscape, holding a separate and powerful position within the hierarchy.

From Mughal to Contemporary Times

In April 2008, the transgenders in Bihar invoked that very era of respect and supremacy when they demanded the same kind of involvement in social welfare policies as existed during the Mughal era.

The study of the Mughal harem and the unique function of eunuchs inside it has great current significance. It is a useful historical resource, providing insights into the complicated interaction between gender identity, societal beliefs, and political power. Understanding historical contexts like the Mughal Empire may give a better-educated basis for these talks in today’s globe when cultures are actively involved in discussions and fights for gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and

diversity.

The Mughal harem’s challenge to preconceptions and conventional assumptions about gender roles and identities is one of its most significant contributions to the current debate. The harem was a multidimensional organisation, with women serving a variety of functions, including administrators, intellectuals, and even politically significant persons. This undermines traditional, binary gender definitions and emphasises the flexibility and variety of gender

identities.

Additionally, the function of eunuchs in the Mughal harem gives a fascinating viewpoint on the agency and contributions of underrepresented groups. In the political order, Eunuchs held a distinctive position as a middle-rung of power. Their acceptance as political players highlights the need to recognise the agency and resiliency of people who do not identify as either male or female.

Credits: Pinterest

The feminist movement now finds resonance in the study of the Mughal harem, especially in postcolonial and feminist literary studies. In later phases of the feminist movement, European feminists started to critically analyse Western depictions of the Mughal harem, seeing that they were oversimplified and based on Orientalist prejudices.

This critical interaction helped to shape intersectional feminist viewpoints that aimed to recognise the variety of women’s experiences and confront Western feminism’s ethnocentric prejudices.

These European feminists used the Mughal harem as a model for their counter-narratives, which praised the independence and tenacity of women in Eastern environments. Contradicting the Western monolithic picture and highlighting the need for a more nuanced understanding of gender, culture, and imperialism, the harem came to represent the variety of women’s lives and experiences.

In conclusion, the study of the Mughal harem and the eunuchs inside it gives great lessons to contemporary society on valuing variety, dispelling prejudices, and advancing equality and inclusiveness in all facets of life. It serves as a reminder that historical narratives are frequently more complex than they first appear and that a thorough comprehension of gender, power, and identity necessitates a willingness to query and transcend crude categorizations and preconceptions.

References

- Lal, R. (2004). Historicizing the Harem: The Challenge of a Princess’s Memoir. Feminist

Studies, 30(3), 590–616. https://doi.org/10.2307/20458986

- Bano, S. (2008). EUNUCHS IN MUGHAL HOUSEHOLD AND COURT. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 69, 417–427. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44147205

- Kalb, E. (2023). A eunuch at the threshold: Mediating access and intimacy in the Mughal world. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 33(3), 747-768.

- Kalb, E. (2020). Slaves at the centre of power: Eunuchs in the service of the Mughal elite, 1556-1707.

- Kalb, E.(2021). Framing Gender in Mughal South Asia. History Compass, Volume 19, issue 11. https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/hic3.12691

- https://servantspasts.wordpress.com/2019/08/12/third-gender-and-service-in-mughal-court-and-harem/

- https://enrouteindianhistory.com/travellers-tales-of-mughal-harem/

- https://indianexpress.com/article/research/eunuch-security-guards-bihar-mughal-empire-history-5266102/#:~:text=Eunuchs%20in%20Mughal%20history,of%20the%20Central%20Asian%20rulers.

Authorship Credits

Vidarshna Mehrotra is a third-year History student at Lady Shri Ram College for Women and a Research Intern at Mandonna.