The moral ambiguity of power is a fascinating topic for young women and examining it through the retelling of Red Riding Hood

When the old woman shows up, it’s never a good sign in the world of fairy tales. She’ll attempt to poison the princess, throw the kids into the oven, or imprison someone in a tower. The archetypal evil old hag is Baba Yaga, the antagonist of numerous folktales from Eastern Europe and Russia. She lives in a hut held up on chicken legs, and if you try to enter, the house will flip itself around to hide the entry. She has a big nose and chin, and when she’s sleeping, she leans over a pole with her gigantic, sagging breasts. She terrorizes kids and, in some tales, devours them. Elderly men often have the opportunity to be wise and magical, like Merlin. Old women just get to be frightening.

This is not how it always was. The witch was as wise as the wizard in the earlier, oral mythology that gave rise to these tales. In today’s society, older women are deprived of their sexuality, power, and attractiveness until they are either hostile or invisible. In three distinct retellings of the Baba Yaga tale, Croatian author Dubravka Ugresic investigates the concerns of ageing and women in Baba Yaga Laid an Egg. She starts off by writing a hilarious and frank essay about her own problematic relationship with her ageing mother and the worry of seeing her deteriorate physically and mentally as she becomes a dotty old hag.

If you were raised Catholic, there comes a time when you will need to reevaluate the stories you were told as a child and consider what you can and cannot reconcile in a world where Magdalene Laundries survivors are fighting for compensation and the church tries to skirt the rape, child murder, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse it was and still is responsible for. I believe there is value in simply trying to grasp and name the things that are challenging to understand.

There is merit in documenting the fact that these events occurred as often as is practical in black and white. Those injured people were then forgotten about. our nation has a history of robbing the weak of their strength and then mistreating them as a result. Other Words for Smoke (by Sarah Maria Griffin) and All The Bad Apples impacted and energized me for a variety of reasons, but also for the strength of examining something extremely horrible from our history and recognising it and expressing what it was. It’s easy, but it’s important.

Raising your voice at all can feel political in a nation that has historically despised and frightened women and the marginalized (and is not currently doing an outstanding job of treating asylum seekers and the destitute like human beings).

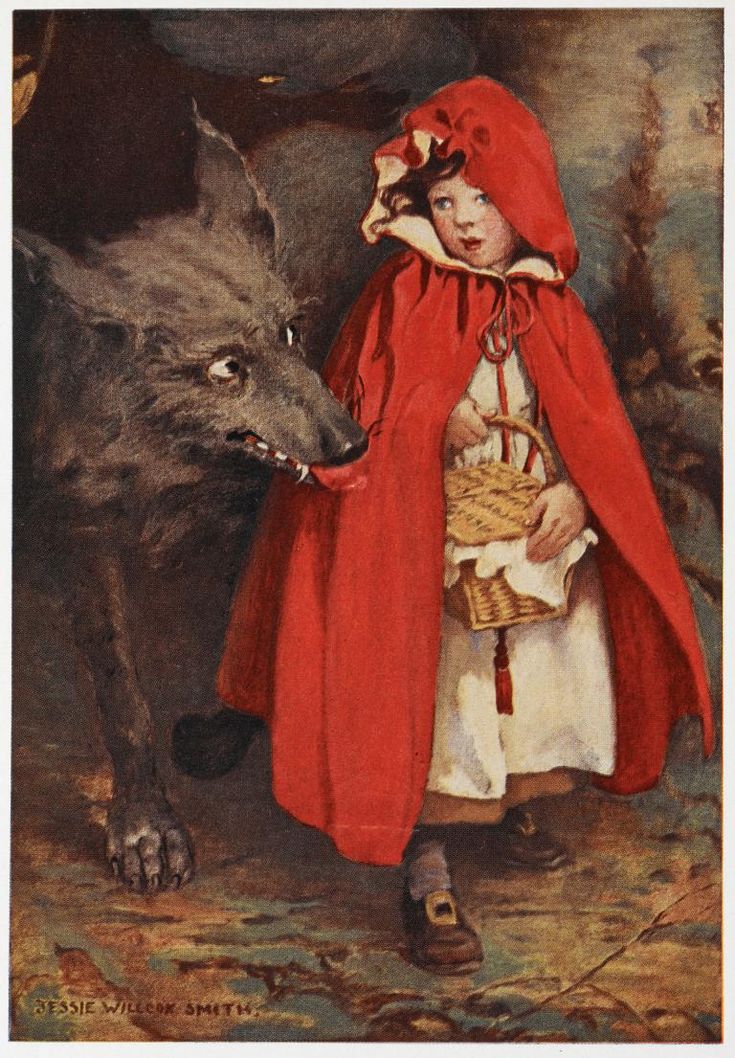

Red Riding Hood was maligned by The Brothers Grimm, but in the old folk tales, she had considerably more bravery. a feminist analysis of both old and modern retellings.

Folktales were first told by peasants, primarily women, as a form of entertainment while working on the laborious duties that took up a considerable amount of their lives. This explains why depictions of women’s labour were so prevalent in the tales, such as the somniferous spindle in Sleeping Beauty, the turning of straw into gold in Rumplestilskin, and the making of clothes out of nettle-flax in “The Wild Swans”.

Fairytales are no longer suitable for all audiences. Really, They’re For Wealthy People.

Fairytales were later appropriated by the French aristocracy and modified to reflect the kind of value system and manners that were considered civilised at the time, despite the fact that these stories were initially seen as lower-class (and we can veer off the beaten path to talk about feminism, poverty, and class if you happen to be doing a women’s studies paper on the topic).

Folktales were an opportunity for women to challenge patriarchal beliefs while exercising their creativity and intelligence. They were typically told as a form of parlour game. These informal gatherings led to the transcribing of tales into writing. Oral storytelling which was formerly accessible to anybody with ears to hear became an exclusive, exclusive activity reserved for the literate nobility and their offspring after it was recorded in writing.

The mythical goddess changes into an evil witch

The original folk stories frequently altered the perspective of women to fit the social norms of the time. The original goddess-figure thus changed into a wicked witch or stepmother, and the active female protagonist changed into an active male hero. Charles Perrault, whose tales are frequently recounted, typically favoured “heroines” who were diligent, polite, and submissive. He likes the women in his folktales and fairytales to always be submissive, upright, and in control

What Role Does Little Red Riding Hood Play in This Situation?

Because Little Red Riding Hood’s story deviates significantly from the ideal, it serves as a warning to young readers. Red goes on an errand for her mother as required, but she stops to talk to “Gaffer Wolf” on the way and this somehow condemns her to punishment. So what if she takes a brief break from her task and converses with a stranger? That’s what happens; Perrault doesn’t provide a nearby woodsman with useful surgical skills, so she gets eaten up.

She is given a second opportunity at redemption by the Grimm brothers, but they emphasise that she has already learned her lesson. Do we have anything to learn from this? Yes, speaking with strange wolves was unethical according to the rules of the day, as Perrault makes clear in the brief, rhyming moral he adds to the end of his tale:

From this story, one learns that children,

Especially young lasses,

Pretty, courteous and well-bred,

Do very wrong to listen to strangers,

And it is not an unheard thing

If the Wolf is thereby provided with his dinner.

I say Wolf, for all wolves

Are not of the same sort;

There is one kind with an amenable disposition

Neither noisy, nor hateful, nor angry,

But tame, obliging and gentle,

Following the young maids

In the streets, even in their homes.

Alas! Who does not know that these gentle wolves?

Are of all such creatures the most dangerous?

Animals are frequently used as symbols for the sexual urge in stories because of their lack of reason and primal inclinations. This metaphor can be expanded to include the role of a sexual predator in a carnivorous animal like a wolf. Even in modern times, we refer to a specific predatory tactic as a “wolf-whistle” when it comes to grabbing a woman’s attention.

In his charming little rhyme, Perrault makes it quite obvious which wolves are the most deadly because they follow young women into their own homes and bedrooms. The moral of the story is that women shouldn’t stop to chat with random men lest they end up in some sort of difficulty.

The moral ethic of the day held that sexual knowledge was perilous and may create a society that was similarly unstable. Being in bed with an odd cross-dressing beast wasn’t the least of Ms Hood’s activities, which were perceived as offences that might lead to death. Also, the way someone dies matters a lot. Red is actually swallowed whole by sexuality when she (symbolically) gives in to her own sexual urges.

An oral motif can be seen emerging with a bit further scrutiny. Red is delivering tasty treats when she stops to talk to the wolf and gets devoured. Of course, there are also the famous last words:

What large teeth you have, grandmother!

“Be A Nice Little Girl Or The Wolf Will Get You,” is the Brothers Grimm’s epigraph.

‘Well-behaved’ or idealised ladies have historically been linked to purity or at the very least propriety in old folk stories. The stories that lead children to become not only physically harmed but also blamed for it later render them docile and without agency. According to the Grimms, Ms. Red and her grandmother are plucked alive from the wolf’s stomach. Grim indeed, but as long as it served a moral purpose, the Grimms had no problem with violence.

She runs upon another wolf on a different occasion, who gives her a courteous greeting. This time, she recognises the malicious expression in his eyes, and with her grandmother’s assistance, she outsmarts him. Thus, the lesson has been learned: never walk alone in the forest, never engage in conversation with strangers, and never, ever allow yourself to become engulfed. Because it will all be your fault for being ignorant and a child.

Blame the woman. calling the woman out. punishing the woman for another person’s wrongdoings. That occurs far too frequently, and the Brothers Grimm made certain it did in the Little Red Riding Hood story as well, calling it a happy ending.

Little Red Riding Hood’s origin story was a more feminist one.

The original folktale, or the variants that have survived, had an altogether different ending from this non-feminist Brothers Grimm version. The term “The Grandmother’s Story” is frequently used in distribution. Although this is an oral tradition with the potential for the teller to freely alter it, in many versions the girl saves herself via her own cunning, and sexuality is handled in a more natural way.

In some versions, the wolf will inquire as to whether she wants to follow the way of pins or needles (yet another reference to “women’s job” in these tales). In some, the girl makes her own decisions, while in others, the wolf might.

Although the girl’s decision has little immediate impact on the plot, it contains inherent meaning. According to seamstress lore, the needle (owing to the eye’s capacity to be threaded) is a sign of sexual maturity, but the pin is associated with chastity. It follows that if the girl takes the road of the needles, she is prepared to accept her sexuality.

Although the girl is provided a sexual option right away, the metaphor of a girl running into a male admirer is still evident.

Aside from the fantastic interpretation of the fable by Angela Carter, Little Red Riding Hood is a complex story that is still highly applicable in modern society. Despite its humble beginnings, the story has been adapted by pop culture and advertising, appropriated by artists, and reimagined by numerous authors and screenwriters. It is also a bedtime favourite for kids.

Little Red Riding Hood live forever. Choose for yourself, sweetheart. Remain steadfast, have one or two useful tools in your basket, and keep an eye out for that wolf.

References

Carter, A. (n.d.). A Feminist Approach to “Little Red Riding Hood” as “The Werewolf”.

Authorship Credits

Kaushiki Ishwar (she/they) is a student at Miranda House pursuing History and Philosophy. Her research interests include feminist epistemology and its intersection with neoliberal cybernetic superstructures. Her favourite philosophers are Zizek, Gayatri Spivak, Judith Butler and Baudrillard.