Although humanitarian help has existed in some form throughout human history, the current definition has only really taken hold in the second half of the 20th century (Rysaback-Smith, 2015). Modern humanitarian help is offered by multiple organisations and individuals as a result of an intricate array of global events, many of which were substantially brought about in response to armed conflicts and natural disasters. However, Gender equality has become a more prominent humanitarian concern in recent decades (Fal-Dutra, 2019). According to CARE International (2021), “With notable exceptions, donors and UN agencies have fallen short of considerably sponsoring women’s groups in fragile and conflict-affected states; seven of the top 11 donors allocated less than 1% of aid to fragile states and directly to women’s organisations”. This article seeks to define what is meant by humanitarian action and how gender disparities are frequently made harsher when a catastrophe strikes. It aims to explain the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of integrating gender into humanitarian action. Moreover, gendered effects of disasters and conflict, like gender-based violence and healthcare, are also covered in this piece.

Humanitarian action is a broad term that encompasses all efforts to help people affected by conflict, natural disasters, or other emergencies. It includes the provision of food, water, shelter, medical care, and other essential services. The goal of humanitarian action is to save lives, alleviate suffering, and

maintain human dignity (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2016). Since it covers such a wide range of actions, it is frequently referred to by several names, including humanitarian help, disaster relief, emergency aid, humanitarian aid, and humanitarian response. It is often a short-term action (can be long term in certain cases), that is an essential part of the international response to crises. It helps to preserve lives, prevent further suffering, and lay the foundation for recovery and rebuilding (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2016).

Credits: Apoorva Jyoti, Graphics Intern at Mandonna

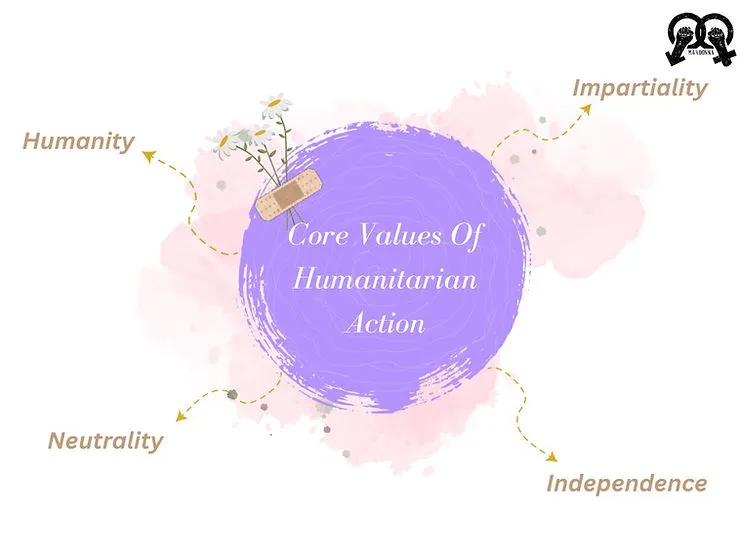

Rysaback-Smith (2015) explains that Humanitarian action relies particularly on four core humanitarian values: humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. These four principles operate in an interdependent manner. ‘Humanity’ encompasses providing aid to those in need, regardless of their location, while upholding the intention to protect and respect all individuals, easing suffering wherever it is found. It is the responsibility of humanitarian organisations to maintain their ‘neutrality’ and refrain from endorsing any specific political, religious, or ideological standpoint. Furthermore, aid must be distributed without considering other factors such as race, nationality, ethnicity, class, political affiliation, or religion, in line with the principle of ‘impartiality’. Lastly, ‘independence’ emphasises the crucial requirement for assistance organisations to remain autonomous and free from any political or military agendas, ensuring that their actions are guided solely by the objective of providing aid.

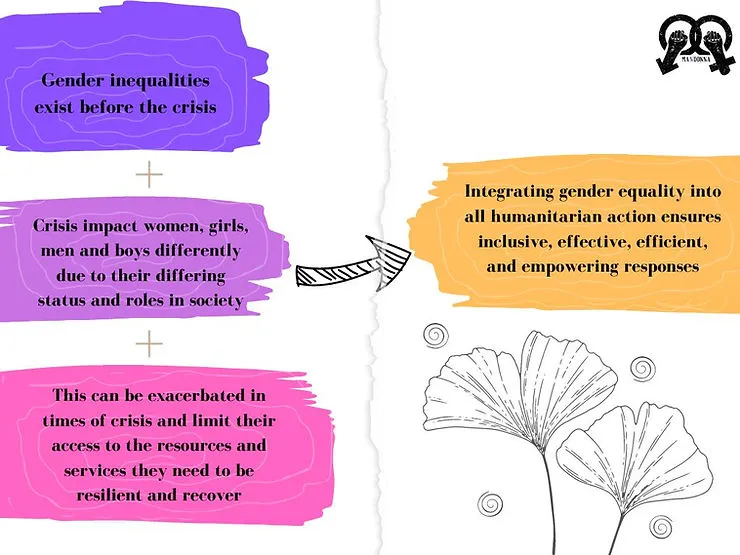

Although these values adhere to the principle of equality, Green (2013) argues that Humanitarian disasters can have profoundly varied effects on women, men, girls, and boys. They can alter societal and cultural norms and redefine women’s and men’s statuses in both positive and negative ways. The needs of people who are most at risk may not be sufficiently served if humanitarian operations are not designed with gender dynamics in mind, and a chance to encourage good change may be lost. Therefore, prioritising gender equality is vital to humanitarian efforts.

The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (2018) states that conflict and natural disasters have distinct effects on different genders, and unfortunately, disasters have demonstrated that fatality rates for women are frequently greater than for men. However, humanitarian actors frequently react based on assumptions about what they think has occurred, including misunderstandings (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012).

During the 2010 Haitian cholera outbreak, given that women are typically the primary carers in Haiti, there was a prevalent belief that cholera disproportionately afflicted women compared to men. As a result, information was frequently aimed at women. When the cholera pandemic in Haiti came to an end, a survey revealed that 67% of the 87 documented cholera deaths in Haiti were men (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012).

In times of conflict, gender-based violence (hereinafter “GBV”) rises. The achievement of gender equality and the enjoyment of rights are hindered by these transgressions. Examples of GBV include rape, sexual exploitation, abuse, forced prostitution, domestic violence, and widow inheritance (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012). The author of this article writes it with a heavy heart that the recent incident in the Indian state of Manipur where two women were gangraped, paraded and molested highlights how these horrific crimes are weaponised in conflicts (Hrishikesh and Mateen, 2023). GBV is a significant, perhaps fatal, human rights, gender, and protection issue that presents special difficulties in a humanitarian setting. According to data by Women, U.N. (2020), It is estimated that 1 in 5 displaced or refugee women have experienced sexual violence; however, given the barriers to disclosure, this number is certainly an underestimate. Most cases of gender-based violence (GBV) involve violence against women and girls (VAWG); however, GBV also affects males and boys (Green, 2013).

The author of this paper also contends that menstrual health and hygiene are often forgotten during crises and should be a large part of humanitarian assistance. Tellier, Farley, et al. (2020) state that Menstrual hygiene products were ranked as a top priority by the estimated 1.4 million women of reproductive age who were impacted by the 2015 earthquake in Nepal.

The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (2018) contends that the strategic link between the humanitarian response and long-term development is gender equality. By aggressively mainstreaming gender equality, humanitarian aid can lay the groundwork for gender equality, reduce risk, and increase resilience against recurring and predictable catastrophes.

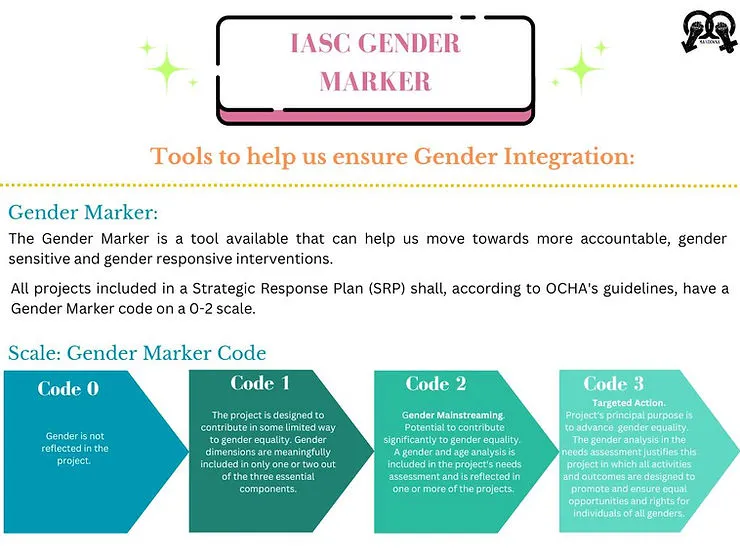

CARE International (2021) states that according to the UN Secretary General’s report on the World Humanitarian Summit’s achievements, the commitment to gender-responsive programming “received the highest number of alignments to a core commitment by UN Member States.” As a result, the UN and donors took steps to better design and oversee programmes to ensure adherence to these gender commitments. In 2018, the UN Inter Agency Standing Committee (IASC) released an updated Gender with Age Marker (GAM), which has aided in raising awareness of gender in interventions and promoting “collaboration, coordination, and accountability” with regard to programming that is gender-responsive (CARE International, 2021).

One example of gender responsiveness can be observed in how during 2017, The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) collaborated on the creation of the Menstrual Hygiene Management “MHM” Toolkit (A Toolkit for Integrating Menstrual Hygiene Management into Humanitarian Response), which is now one of the primary reference guides for MHM mainstreaming in emergency programming. MHM materials and supplies, MHM supportive facilities, and MHM information are the three main components of MHM programming in crises that are included in the toolkit (UNFPA, 2020). To guarantee that MHM is tackled holistically, the MHM toolkit advises a strong relationship between the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector and the other humanitarian sectors (UNFPA, 2020).

In conclusion, addressing the specific requirements and vulnerabilities of women, men, girls, and boys in times of catastrophe requires integrating gender into humanitarian action. Although the goal of humanitarian aid is to preserve lives and lessen suffering, gender inequalities frequently worsen when catastrophes strike. Gender-based violence increases and women’s death rates can be disproportionately greater during conflicts. The lack of access to healthcare has a negative impact on maternal and child health, and menstrual hygiene requirements are routinely disregarded.

Gender equality needs to be prioritised in humanitarian operations if we’re going to get more effective and inclusive results. To do this, it’s important to question presumptions and consider the various ways that disasters and conflicts affect people of different genders. Support for women’s groups in fragile and conflict-affected states must come from donors, UN agencies, and humanitarian organisations. With promises to gender-responsive programming and the creation of tools like the Gender with Age Marker (GAM) and the Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Toolkit, efforts to incorporate gender equality in humanitarian action have gained pace. To make sure that gender issues are incorporated into humanitarian actions, these projects encourage collaboration, coordination, and accountability.

We can develop more resilient and long-lasting solutions to crises, lower risks, and create a more just and equitable society for all if we embrace gender equality in humanitarian action. It is critical to keep pushing for gender equality in humanitarian contexts and to promote projects that speak to the unique needs and rights of different genders.