As Judith Butler argues that "Gender is not a noun, but a verb, an action, a performance". She contends that while it is important to recognise and respect diverse gender identities, it is also necessary to challenge the rigid gender norms and expectations that underlie gender-based oppression.

Credits: NY Times (Hijras in India)

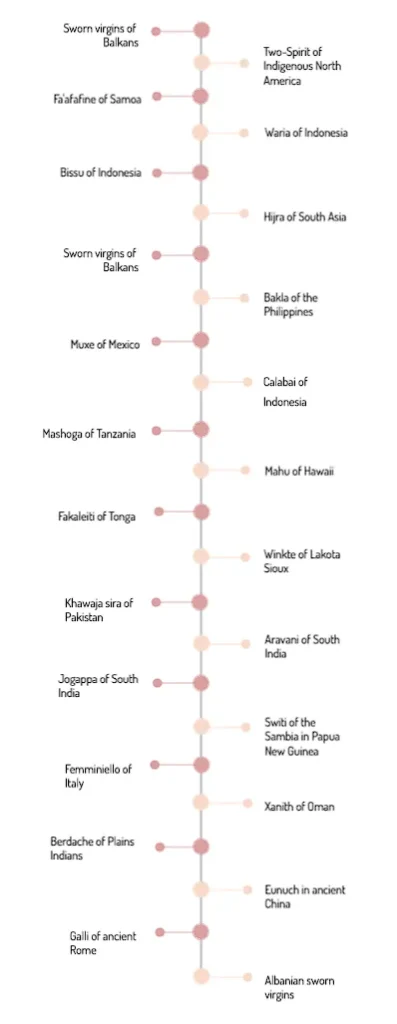

Gender identity is a complex and multifaceted concept that has been studied and debated for centuries. In many cultures throughout history, the binary concept of male and female has not been sufficient to encompass the diversity of human gender experiences. Instead, a third sex or gender category has been recognised, acknowledged and even celebrated. This third sex or gender category can be found in many cultures around the world, from Native American Two-Spirit people to Hijras in India to the Sworn Virgins of Albania.

Outline of the Article

In this article, we will explore the concept of third-sex and third-gender identities from a historical perspective. We will also examine the ways in which these identities were recognised and understood in different cultures throughout history and how they were perceived by those within and outside of these cultures. We will also examine the ways in which third-sex and third-gender identities have been suppressed or erased over time, particularly in the wake of colonialism and the imposition of European gender norms on non-European culture.

Third sex and Gender Identities in Different Regions

DEFINING THIRD GENDER IDENTITIES

While there is no universally accepted definition of third gender identities, scholars have offered a range of perspectives on what these identities are and how they should be understood.

One perspective on third-gender identities emphasises the cultural and historical context in which they emerge. Anthropologist Serena Nanda argues that third-gender identities are social constructs that emerge within specific cultural contexts, reflecting the complex interplay between gender, sexuality, and power. Nanda contends that understanding third-gender identities requires an appreciation for the ways in which gender and sexuality are constructed and negotiated within specific social and historical contexts. She emphasises that these identities cannot be understood in isolation from the cultural beliefs and practices that shape them.[1]

Another perspective on third gender identities emphasises the psychological and biological dimensions of these identities. Psychologist Anne Vitale argues that third gender identities are the result of an innate sense of gender identity that does not conform to traditional male-female binaries. Vitale contends that third gender identities are a legitimate expression of human diversity and should be recognised and valued as such. She emphasises that these identities are not simply social constructs but are rooted in the biological and psychological experiences of individuals who identify as third gender.[2]

Social theorists have provided various definitions and understandings of third gender identities. One notable social theorist who contributed to this discourse is Judith Butler. In her book Gender Trouble, Butler challenges the traditional binary understanding of gender as either male or female and argues that gender is a social construct that is continually performed and reproduced through language and cultural practices[3]. She suggests that the category of gender is constructed through the repeated performance of gendered acts and that these acts are not necessarily based on a natural or innate sex difference. Butler’s understanding of gender as performance has significant implications for the concept of third-gender identities. She argues that the very existence of third-gender identities challenges the binary and hierarchical system of gender that is deeply embedded in Western culture. According to Butler, third gender identities expose the ways in which gender is constructed and maintained through social norms and cultural practices and offer a radical critique of the traditional gender binary.

Another notable social theorist who has contributed to the discourse on third-gender identities is Michel Foucault. In his book The History of Sexuality, Foucault argues that sexuality is not a natural or innate characteristic of human beings but rather a social construct that is shaped by cultural and historical factors[4]. He suggests that the construction of sexuality is closely linked to the formation of power relations and that the regulation of sexuality is a key mechanism through which power is exercised. Foucault’s understanding of the social construction of sexuality is relevant to the concept of third-gender identities, as these identities are often linked to non-normative forms of sexual expression or desire. Foucault’s analysis of the regulation of sexuality provides a framework for understanding the ways in which third-gender identities are policed and controlled by social norms and cultural practices.

In addition to Butler and Foucault, other social theorists have contributed to the discourse on third-gender identities. For example, Gayle Rubin’s concept of the “charmed circle” offers a way of understanding the ways in which certain sexual practices and identities are stigmatised and marginalised within a culture. Rubin argues that the stigmatisation of non-normative sexual practices and identities is based on a moralistic and often arbitrary distinction between “good” and “bad” forms of sexual expression.[5]

The concept of the third gender has a long history in many cultures around the world, where the identities are far more fluid than the existent structures.

In several African societies, there are cultural practices that recognise third-gender categories, such as the Swahili culture of Kenya and Tanzania; there is a third-gender category known as Shoga or Mashoga. This category includes individuals who are assigned male at birth but who are seen as having feminine characteristics and who may engage in same-sex relationships. The Shoga are recognised and respected members of Swahili society and are often involved in traditional cultural practices such as music and dance[6]. Similarly, in the Hausa culture of Nigeria, there is a third gender category known as Yan Daudu, which includes individuals who are assigned male at birth but who identify and behave in ways that are typically associated with women. The Yan Daudu are also recognised and respected members of Hausa society and are often involved in traditional cultural practices such as music and storytelling.[7]

Even various Latin American societies recognise cultural practices of third gender categories. One example is the Muxes of Oaxaca, Mexico. Muxes are individuals who are assigned male at birth but who identify and behave in ways that are typically associated with women. The Muxes are recognized and respected members of Zapotec society, and they are often involved in traditional cultural practices such as weaving and embroidery.[8]

Many Native American cultures recognise the existence of third-gender or Two-Spirit individuals, who often hold a respected and honoured place in their communities. The term Two-Spirit is a modern umbrella term used to describe the diverse range of traditional gender identities and roles of Native American people who identify as having both a male and female spirit[9] For example, the Navajo people of the southwestern United States recognise a third gender called Nadleehi, which refers to individuals who possess both male and female characteristics. Nadleehi are believed to possess a sacred balance of male and female energies and are often valued as healers and mediators.[10]. Similarly, the Lakota people of the Northern Great Plains recognise a third gender called Winkte, which refers to individuals who are biologically male but who assume a feminine gender role. Winkte are often regarded as spiritual leaders and are highly respected for their ability to mediate between the spiritual and physical worlds[11]

In both cases, the recognition of third-gender categories reflects longstanding cultural traditions that value and respect diversity in gender identity and expression. As in Pacific Island societies, third gender identities, such as the Fa’afafine of Samoa. Fa’afafine are individuals who are assigned male at birth but who identify and behave in ways that are typically associated with women. The fa’afafine are recognised and respected members of Samoan society, and they are often involved in traditional cultural practices such as dance and song.[12] Another example is the fakafefine of Tonga. Like the fa’afafine, the fakafefine are individuals who are assigned male at birth but who identify and behave in ways that are typically associated with women. The fakafefine are also recognised and respected members of Tongan society, and they are often involved in traditional cultural practices such as dance and ceremony[13].

THIRD GENDER IDENTITIES: LEGACY OF COLONIALISM.

One important aspect of this exploration is the recognition of third-gender identities in non-European cultures, which have often been suppressed or erased as a result of colonialism and the imposition of European gender norms. As Susan Stryker notes, “Colonialism played a significant role in erasing non-normative gender identities and sexualities and replacing them with European models of gender and sexuality.”[14]

One example of a society that recognises third-gender identities is the Hijra community in India. Hijras are individuals who were assigned male at birth but identify aas female or as neither male nor female. They are considered to possess special spiritual powers and are invited to perform at weddings and other important ceremonies. However, the colonial-era Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 criminalised hijra identity and forced hijras into hiding, perpetuating a legacy of marginalisation that continues to this day[15]

Similarly, many Native American cultures recognise the Two-Spirit tradition, which encompasses individuals who embody both male and female spirits. Two-Spirit individuals are often considered to have unique spiritual gifts and are accorded special roles in their communities. However, the forced assimilation of Native American cultures by European colonisers has led to the suppression of the Two-Spirit tradition and the erasure of non-binary gender identities[16].

Another example of a culture that recognises third-gender identities is Albanian culture, which includes the tradition of the Sworn Virgin. Sworn Virgins are individuals assigned female at birth who take a vow of celibacy and live as men. They are accorded special social status and are often seen as embodying both male and female qualities[17]. However, the imposition of communist gender norms in Albania during the 20th century led to the suppression of the Sworn Virgin tradition.

Towards the End

References

[2] Vitale, Anne. The Gendered Self: Further Commentary on the Transsexual Phenomenon. New York: Harrington Park Press, 1997

[3] Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990, 35.

[4]Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage Books, 1990, 37.

[5] Rubin, Gayle. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” In Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, edited by Carol S. Vance, 267-293. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984, 271.

[6]Nanda, Serena. Neither Man Nor Woman. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1998..

[7] Murray, Stephen O. The Hausa ‘Yan Daudu: A Gender and Sexuality Study of Effeminacy in Nigeria. New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

[8]Burrington, Carl. Muxes: Authentic, Intrepid Seekers of Danger. London, UK: Emblem Editions, 2017.

[9] Jacobs, Jerry B., Donald J. Thomas, and Kenneth Lang. “A Theory of Political Discourse as a Spatial Process.” The Journal of Politics 59, no. 4 (1997): 1267-1290.

[10] Roscoe, Will. The Zuni Man-Woman. Albuquerque: the University of New Mexico Press, 1993.

[11] Jacobs, Thomas, and Lang, “A Theory of Political Discourse,” 1275.

[12] Besnier, Niko. “Polynesian Gender Liminality through Time and Space.” In Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History, edited by Gilbert Herdt, 285-327. New York: Zone Books, 1994.

[13] Schmidt, Ute. “The Third Sex: Kathoey–Thailand’s Ladyboys.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 9, no. 1-2 (2003): 41-68

[14]. Stryker, Susan. “Transgender History, Homonormativity, and Disciplinarity.” Radical History Review 94 (2006): 20-28.

[15]Nanda, Serena. Neither Man Nor Woman. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1998, 94.

[16]Roscoe, “Queering the Saddle,” 123.

[17]Young, A. (2000). The Sworn Virgin: A note on the relationship between gender and power in Albania. Anthropological Quarterly, 73(3), 113-120.

[18] Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble, 144.

Drishti Kalra is an Assistant professor at DCAC College in the Department of History, at Delhi University. She is also a PhD Research scholar at the Department of History at Delhi University. She has also been employed as a Research Assistant on two projects at the Max Planck Institute in Germany and JNU. Currently. She has lately held positions with institutions such as The Telegraph, Médecins Sans Frontières, Intern, and Hindu Business Line.